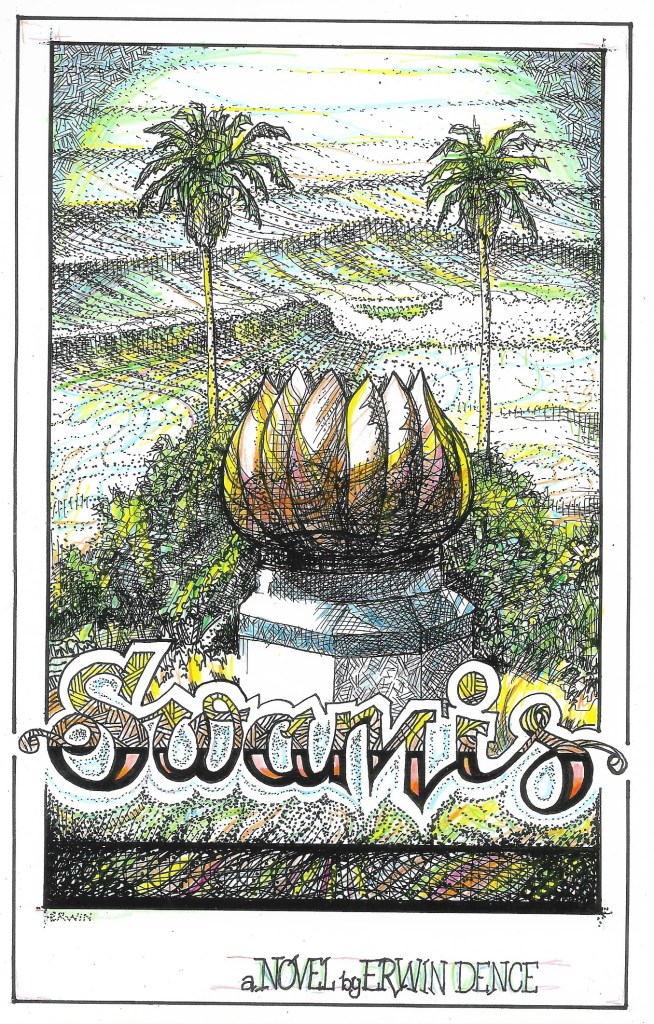

MY NOVEL. Erwin’s Opus. It seems like I’ve been working on it forever. Writing, writing, editing, cutting, reworking. With tens of thousands of words sliced and phrasing polished, side stories removed, characters dropped, the timeline shortened, the storyline tightened, a hundred little inconsistencies fixed, I am almost, for at least the fourth time, approaching the end.

DO I have some faith that this version of the manuscript is reader friendly, like, commercial, like, perhaps, some novel you might consider for a casual read?

NO. Put it down to stubbornness, perhaps. My acceptance that I had to make changes to make “Swamis” readable is in a battle with my desire to make the fictional real.

I HAVE DECIDED TO start publishing “Swamis” in serial form on this site. BECAUSE I have committed to doing content on Sundays, I will start with the INTRODUCTION and post pages on WEDNESDAYS.

“SWAMIS” INTRODUCTION

It was a conceit, I now can see, my belief that I had a gift. I could visualize, actually see, in my mind, what I had just witnessed. I could store this visualization, file it with others, bring it back into my mental vision at will. Memories. Not all memories. Important ones. Images of things I’ve seen, audio of words heard. Or overheard.

Ridiculous. We all seem to have this ability. If developed, it becomes a skill. My not realizing my own ridiculousness when I was seventeen may have been to my advantage.

Or maybe that’s just how I remember it.

My father was a detective. “What do you see?” That was always the question. Little things: A bent spoon, spilled milk, eyes that evade, words that contradict. Clues. Evidence. “What does it all mean?” The tougher question. “The greatest theory,” my father would say, “is nothing compared to the tiniest truth.”

Still, I noticed as many of the little things as I could. I tried to notice everything. Partially because I trusted my selected groups of clues, my biased interpretations, even less than I trusted the words and motives of others, I kept notes. Years and years of notes.

If I can’t seem to pull some vague memory out of my files… notes.

Memories, I have come to believe, have lives; a pulse of their own that we, as hosts, can push aside or ignore, try to forget, or try to pretend some memories were not real; we can place a memory in with enough other memories and dreams and fictions and secrets and lies that we can, briefly, convince ourselves that, at some time, in some situation, under some condition, the truth of that repressed memory will not come back to hit us, full force. If the truth of that secret, that lie, is revealed, we fear, our lives will be changed. Full force.

We cannot, continuing my overthinking, completely delete or erase even a pleasant memory, a mundane memory. All memories are somewhere.

I had an image, in some place between dream and awake-ness, of little containers, something to hold a bar of soap on a quick trip. Plastic, lid fitting over a tray. There were many of these containers, some larger than others, moving up and down vertical lines, something more like ropes, three strands, weaved. The containers were white because, supposedly, men lack enough imagination to dream in color. The ropes, I would swear, were greens and reds. The background was definitely black.

It was a dream. I knew that. i did have enough imagination to convince myself that these containers held memories. Why not? There was movement, forces from the side, a wind, possibly, bumping one line into another, that one into the next one. Not chaotic but almost controlled movement. Almost a dance. And there was a beat. Background. The pulse thing. Almost music.

Trying to stay in the dream; trying to hold the moment; I theorized that memories are as much in our blood streams as in our brains; definitely not as cataloged and compartmentalized as we tell ourselves, and definitely not as controlled.

Perhaps, if I opened this one container…

I couldn’t. Or I woke up before I could open it. I was aware of my surroundings. Saturday, December third, two thousand and twenty-two. Briefly aware. I slipped from dream to memory.

I was paddling as hard as I could. A wave, already breaking to my left, was bearing down on me. I felt the wind push the top off the foam on the already lifting surface of the water, the remnants of the larger wave before this one coming up the face. I was aware of the heaviness and the speed of my breathing. I felt the lift and the drop and the weightlessness and the catching of my weight on my board. Instant rebalancing, pressure with my right foot on the inside rail. Swing. I turned. I had to rise, had to go faster. I did. Again, weightless, the low sun flashed off the wave face. Gold, white, too bright. The curve of the wave, yards ahead of me, was impossibly steep, the lip feathering, throwing itself forward, lace and diamonds and rainbows. I had to keep my eyes open. Had to. I was in the tube. I was elated. The very few seconds were magical and terrifying.

The knock down was not as violent as I would have thought. Had I thought. The lip hit me. There was no recovery. My board slipped and skittered and went sideways. It was six feet down to the trough, sideways to upside down to down, six feet of wave pushing me. My body was curling and straightening under the power and the weight, pushed six feet under water, to the bottom, tumbling, caught in the surge, and struggling. Uselessly. I came up fifteen feet over and twenty feet closer to shore. Another broken wave hit me before I could cough out and take in another breath.

Three rides on a day that would become legendary was enough. I stood up in the shallows, the sea grass covered rock ledges that were like ever extending fingers from the cove to the point. I would pick my way to shore, collect my board, and head for the stairs. Three rides. Two on waves other surfers had fallen on, one magic tube ride on a wave that was just mine. Magic. No shame.

No board. I looked around. There were other surfers on the beach, those who had failed and those waiting to build enough nerve to go out. The steep cliff was still in a shadow that extended halfway out to the inside peak. I looked up. There were silhouettes, trees and a line of people, spectators at the stadium. All of them seemed to be pointing out and yelling in unison. I couldn’t quite hear them. Three surfers on the beach joined in. “It’s in the rip! It’s in the rip!”

I had to swim back out. Had to.

The same rip current that had taken my board, down the beach and around the biggest of the waves, created enough of a channel that surfers whose skills did not match the conditions could get to the lineup. Fools and heroes. Just witnessing great surfers on great waves was enough for some of them. Five surfers would back off as another, thirty yards deeper, would scream toward and then under and then past them, Santana winds blowing back fifteen feet from each breaking wave. Occasionally a fool would take off in front of someone who just might make the wave. Fools and heroes and witnesses, spectators with cameras on the bluff.

I had just reached my board. It was floating, right side up, just beyond the regular takeoff spot for the inside peak. Someone yelled, “Outside!” Everyone started paddling, desperately, toward deeper water. A young woman dropped in, two stroke takeoff, on the first wave, fifty yards out and forty yards up the point from me. She seemed to be standing, effortlessly, she and her board separately freefalling to the bottom third of the wave. She landed, toes first, and rebalanced, moving her right foot back. She cleanly and gracefully leaned into the wave, her body stretched, her left arm pointing down the line. Despite the strength of her turn, she seemed to glide up to the top third of the hollow pit. She crouched, tight, disappeared even from my view, in the glare and the gold and the diamonds and lace. She reappeared, sideslipped, put her right hand into the face of the wave, reconnected, and, with the lip of the wave throwing itself out and over her head, and with the biggest smile possible on her face, she looked directly at me and screamed, “Joe-y!”

I screamed, “Ju-lie!” Julia Truelove Cole. Swamis. Tuesday, December second, nineteen-sixty-nine. Fifty-four years ago, as I write this, and… And Julie made the wave.

I am fully awake now. I can visualize all of this in living, vibrant, real-to-life color. It is real to me.

“Swamis” is a memoir, of sorts, memories of Joseph Atsushi DeFreines. “Swamis” is not a surf novel but a surfer’s story. “Swamis” does not fit comfortably in the detective/mystery genre. Writing and rewriting “Swamis” would have been so much easier if the narrator hadn’t been caught up in the back stories and the side stories, the tangents and the overlapping circles. After countless hours remembering and thinking and writing, editing and deleting, of trying to fit what I want to say in some format a reader would recognize, I might have to say “Swamis” is mostly a coming-of-age/romance novel set in a very specific, magical and terrifying time and place.

I apologize in advance for telling too much about minor characters, for side trips into the periphery. I refuse to apologize for the enjoyment I have had, so many years on, opening and reopening those containers. Of those I stories I have deleted: They’re somewhere, some backup file, some thumb drive. Of those I so feared opening: I have opened them now. I had to.

“Swamis” is copyrighted. All rights reserved by Erwin Dence.

Enjoyed the intro!