This is going to change. Every time I look at this, I seem to start at the beginning, move, slowly, on toward where I want to be, that being writing more, new stuff. The great part is, as the plot develops, I can go back and change things to make the story better. Better is what I’m going for, great. It’s not there; yet; but I’m working on it.

SWAMIS ‘69

SECOND WEEK OF JUNE, 1969- PERIPHERAL VISION

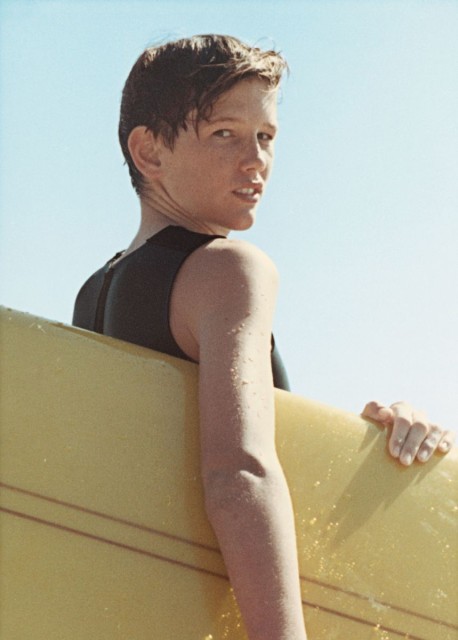

Almost leaping from stair to stair, I was looking at the water, the fuzzy horizon, the lines; counting, then recounting the surfers already in the water; trying to beat any other surfers who missed the true dawn patrol. Swamis was, finally, it seemed, breaking; tide dropping; swell, hopefully, increasing. It would get crowded.

Two surfers were walking from halfway up the point, along the water’s edge. I wasn’t focused on them; they were shapes, so familiar; surfer and board, nose-up or nose-down, more-or-less crosses in the grainy light, the shadows of the bluff. One was walking faster, trying to catch up. “June,” I heard, or thought I heard; then, more like a question, “Junipero?” Then, closer to the guy in front of him; “Jumper.”

“Jumper,” I thought. Jumper. Now I almost focused.

Almost. It was a moment, still just a moment, between a surfer reaching for, and touching the other man’s shoulder- it was Sid, reaching; Sid, a locally-known surfer; Surfboards Hawaii team rider; known to thrash his boards; known to take on crazy waves, to burn valley cowboys and out-of-town surfers, even Orange County magazine surf stars down to trade crowded beach breaks for a chance at Swamis point break magic- Sid, featured in a small, grainy, black and white ad in “Surfer” magazine.

I must have blinked. Sid was flat-out, on his back, parallel to that line where the sand turned hard with the receding tide. His board was floating in the shallows, Jumper’s board pressed, nose-first, to his neck; Jumper’s foot on his chest.

Jumper. Fucking Jumper. He was back in town, back at Swamis.

If we could just ‘backspace’ time ten seconds, not all the time, but for those moments we witnessed but couldn’t immediately process. Maybe ‘replay’ is more accurate. Ten seconds.

Fifty years gone, I’m trying to replay moments, bits and fragments and images and strings; strings of time; so many strings; some tangled, some free.

Oh, I broke free of the North County scene years ago; lost my contacts, forgot names, confused and overlapped stories from Grandview and Pipes and Cardiff Reef. I do still remember specific rides among thousands; remember, almost precisely, the times I was injured; held down, hit the bottom, was hit by someone else’s board; but, and I’ve tried, I can’t remember Sid’s last name.

But I remember Jumper.

In another moment, with me even with them, trying to be cool, to not look, both surfers were sitting on Jumper’s board. Peripheral vision. No, probably did turn my head. Never was cool.

Jumper’s hair was shorter than mine, but, even with the patchy start of a beard; he was still recognizable, the same guy from, probably, four years earlier, back when I was just switching from surf mats to boards; back when he caught any wave he wanted any time he showed up. The Army or prison; stories about his disappearance varied; rumors among high school friends who quoted various upper classmen, scattered pieces from other people’s beachfire conversations.

“I heard he moved to Hawaii,” or, “No, Buttwipe; Australia. Or New Zealand.” Or, “Chicago.” “No fucking way.” “San Francisco, then.” “Nooooo.”

Then someone would go into a Jumper surf impression, with play-by-play commentary, on any nearby surfboard; Right arm back, elbow cocked, hand like a conductor’s, flowing with the up-and-down movements on the imagined wave; subtle, the left arm lower, hand out flat; punctuated with, rather than the classic cross step to the nose, the quick shuffle, the jump; then a crouch and a shift to a more parallel stance, right hand in the wave, left hand grabbing the outside rail. Twist, weight forward; the fin would pop out of the sand.

“Island pullout.”

Someone else would repeat the performance, only, left foot on the tip in a solid five, upper torso shifting to face the wave, arms spreading wide; he would pull the skeg, make the rotation, yell, “Standing island pullout”, and shuffle back on the board, casually drop to his knees, ready to paddle out.

Yes, I participated in this. Yes, I tried to develop that “Jumper” conductor-dancer flow on my skateboard, pivoting, slaloming down my block, on inland hills, miles from the ocean. I had a long enough board, eventually, to go with the cross step; more like Phil Edwards, Micki Dora.

Style.

Jumper was probably my second surf hero. Maybe third. Heroes dominated lineups. Kooks and kids gave way, gave waves, watched them, always trying to stay out of the way. Now this same Jumper was, quite possibly, crying, one hand on Sid’s shoulder, one of Sid’s on his. It was Sid who looked around at me with a ‘fuck off’ look.

Peripheral. No, I’d looked back.

I looked away, kept walking. Still only a short distance away, I did what every surfer does, and always has; studied the ocean for a moment before committing; disciple before the alter.

When I looked back, from out in the water, from my lineup, the inside lineup, Sid and Jumper were half way up the stairs. Sid was one step ahead, one above. When two guys came down, Sid, probably because he didn’t know them, or because he did, made the down-stair surfers split up and go around. Jumper moved behind Sid’s block.

A set approached. Surfers, who had been straddling their boards in the lull, dropped to prone, started paddling. At this tide, some of the waves from the outside peak were still connecting all the way through. The first one didn’t; the surfer on it lost behind a section. Two surfers went for the shoulder as I stroked past. The second wave swung wide, peaked-up on the inside. I had it to myself; another takeoff, drop, turn, cutback, back and forth to the inside inside, fitting my board into and through that last little power pocket, peeling over the palm of the finger slabs that opened to the sea. A little standing island pullout into the swampy grass. Swamis.

THIRD WEEK OF JUNE- PEACE AND FREEDOM AND REVOLUTION

If the Noah’s Ark trailer park wasn’t still there, there on the north end of Leucadia, yet another trailer park squatted up against yet another bluff along 101, protected from the south winds; if it wasn’t still there in 1969; it had been there on those trips with my family, down the coastal route to San Diego.

I understand there’s a jetty there now; Ponto.

I also can’t clearly remember if the fields north of Grandview, the original Grandview, the fields along those bluffs were fields of tomatoes or strawberries. I know there were no houses. There were the Leucadia greenhouses. Flowers. It was what Leucadia was known for. Poinsettias.

Maybe not these particular greenhouses.

Turning off 101, I drove past several. One, and this had been pointed out to me by more than one of my high school surfing buddies, belonged to the family of Jumper Hayes. On this morning, still dark, what the forecasters called ‘early morning and evening overcast,’ or ‘June gloom’ hanging on, almost misty; I saw Jumper’s old pickup, almost-flat paint a weird shade of green in the light of the yard lamp, parked outside one of the greenhouses. Only the tail, fin over the tailgate, showed this farm rig was a surfer’s vehicle.

I gave myself a bit of a self-congratulatory nod, a quick smack on the shifter, three-on-the-tree; double-clutched down to second, gunned it.

It had become my workday predawn move, up and down Neptune, checking out Grandview, Beacons, Stone Steps; possibly surfing whichever one had a more consistent peak. Or a peak at all. If it was bigger, big enough, I would push the fourth-hand Falcon station wagon farther, along the bluff, passing the increasingly-fancy houses blocking any view of the water, to another low point between the bluffs, Moonlight beach. Rarely surfed there. I’d then go up, cruising past even fancier homes, then around the thick white walls and the gold bulbs of the Self Realization compound, the reason Swamis is named Swamis, to Swami’s Point.

The little park had an official name, Seacliff Park, I think; long since replaced. Swamis.

Or, depending on my hours; when I got off work, I would turn onto 101 at Cardiff reef, pass the state park, try to get a glimpse of Swamis over the guardrail. If it was breaking big enough, you could see it. I would hit the parking lot and get out. Even if it wasn’t breaking, even in the dark, I’d check the view from Boneyards, past what my high school friends and I called Swamis Beachbreak, onto and beyond Pipes, the galvanized culverts, at that time, still shiny, protruding fifteen feet or so out of the sandstone bluffs.

Maybe there’d be some last-lighters, still hanging in the parking lot; their stories of new and past glories punctuated with a hoot or a laugh; headlights and streetlights in a descending darkness and a dim glow from the horizon.

Swamis was where I wanted to surf. June gloom or bright offshore glare; breaking or not. What I felt, and was totally aware of feeling, was that my choice of route and destination was mine, mine alone; that I was pretty fuckin’ close to being free.

Within reason, of course.

………………………………..SO FUCK-ING COOL, MAN

For a short period of time, but right about this time; well past ‘groovy,’ way past anyone remotely cool (or young) calling anyone a ‘Hippie,’ I made the adjustment, from ‘fuckin’, dropping the ‘ing,’ to Fuck-ing, emphasis on the ‘ing.’ This was after running into a guy, Gordie, from my high school at a liquor store in Vista. He now, suddenly, sporting long hair (longer- Fallbrook had a dress code and we’d just graduated), parted in the middle (of course), and clothing that denied his quite-upper class upbringing. “So fuck-ing cool, man. We just don’t fuck-ing see each other, man; like, like we used to.” And he was, obviously, stoned, an even more-stoned girl, possibly still in high school, headband, boutique-chic top, nodding, eyes unable to focus, next to him. Gordie put a hand on my shoulder. I looked at his hand, put my package of Hostess donettes and quart of milk on the counter, pointed to a pack of Marlboros, turned back to Gordie. He sort of gave me a look when I scooped up the cigarettes. “I know, man… Gordie; you probably don’t fuck-ing smoke… cigarettes.” He and the girl both giggled. So uncool. “Peace, man.”

Yeah, flipping the peace sign was, also, probably pretty much over.

On special occasions, perhaps; what we would only later refer to as ‘ironically.’

My relative freedom isn’t, perhaps, relevant to the story. Maybe it is; these were times when ‘freedom’ and ‘peace’ and ‘revolution’ were frequently used in the same sentence. For someone just out of high school, working various shifts at a supermarket with a view of the ocean; joy and loneliness and a sense of being part of some grand mystery could all be felt in a very short span of time; and repeated, randomly. Mysteries.

Why, I had been asking myself, did Sid call Jumper ‘June?’ June with a hard J; not a H sound. If his real name was, say, Jesus; well, anyone would instantly know it’s not Jesus, like Jesus Christ, but Hey-Seuss, like Hey, Doctor Seuss, dropping the ‘doctor.’

Mysteries ask to be solved. Beg, perhaps. Rumors. Surfing, waves, surfing waves well; that was a mystery. Board surfing was more than just drop and hang on. Tamarack was obvious; one peak in front of the bathrooms on the bluff, a bit of a channel; a parking lot at beach level. Good place to learn; sit on the shoulder; wait, watch, study; move toward the peak; a bit closer with each session. Get yelled at; get threatened; learn.

Eventually, you would have to challenge someone for a wave.

………………………………………………..INLANDNESS

But there were always rumors of better waves, great waves, magical and secret spots, places uncool freshmen kooks weren’t supposed to know about, weren’t supposed to show up at.

Grandview was fairly easy to find. There was a Grandview Street off 101 in Leucadia. Still, when I showed up there with my friends, now sophomores, we got looks. Punks, Kooks; not ready for Grandview. The hardest looks were from other San Marcos, Vista, Fallbrook, Escondido surfers; other inland cowboys.

Inlandness was, and still is, in direct proportion to distance from the coast. Where I lived, Fallbrook, we called Escondido Mexican-dido. That was, of course, insensitive. Maybe; but I understand Meth-condido has replaced it.

As with, probably, anywhere, you had to persist. I did. As my contemporaries and I searched out new locations; San Onofre, occasionally Oceanside; as some dropped surfing, traded it for parties fueled with liquor purchased by willing Marines (bribed with “I’ll buy if you fly”), marijuana bought from friends of friends, I had become another surf addict; and Grandview was still on my route.

By the end of my senior year, I had become accustomed to going surfing alone.

And now, here I was, almost recognized as a local, slipping and sliding down the more-sand-than-sandstone between houses, original Grandview, the real Grandview; and ahead of the ultimate local, back after four years or so, Jumper Hayes.

Just ahead.

Peace and freedom and revolution.

MARCH OF 1969- SHERWOOD FOREST AND THE EMERALD CITY

I have to drop back for a moment. The story hinges on this. Chulo Lopez had been killed, murdered. His real name wasn’t Chulo; nickname; I can’t remember his real first name. It was in the paper, even on the San Diego TV news. “Horrific” the studio commentator said. “The San Diego County Sheriff’s Office reports Mister Lopez, a well-known surfer, was probably dead… probably… when his body was ‘posed’ against the thick white walls of the Self Realization Fellowship compound, doused with gasoline, and set ablaze. Set ablaze.”

The commentator’s face remained on the screen just a moment too long, mouthing ‘set ablaze’ with just a bit of a smile before a younger, hipper man appeared, turned toward the camera, swung his microphone close to his face. “It’s a frightening scene here in the North County,” he said.

The reporter stepped aside. The camera panned the crowd of surfers, non-surfers, behind the rope; some giving expressions of shock, others looking away. The angle slowly moved in, past the firefighters and cops, just milling about or talking in groups of two or three. The blackened areas on the white white stucco-over-brick walls formed a sort of outline, the darkness around a candle’s flame.

The TV camera followed the burn marks up to the gold bulbs atop the wall. There was a sort of symmetry, a repetition. “Set ablaze.”

Chulo’s body, remains, had, of course, been gone long before the TV crew arrived.

My brother, at my mother’s insistence, had awakened me to watch the report on the late news. Channels 4, 8, and ten; those were our choices in the Fallbrook, several L.A. stations if someone climbed on the roof and moved the antenna. Since it was the lead story on each of the channels, my mom chose channel 8; the commentator was her favorite.

I recognized a couple of the onlookers. Some were Surfers; some Tourists, with an itinerary; some grown-up, Working People taking a lunch break. Others were Hodads and/or part-time Hippies, interchangeable characters. There always seemed to be a few of these folks hanging around, along with the ‘the Hippie Movement is dead, man’ Hippies. The Hodads and the ‘yeah, I used to surf; back in the old days’ Liars and legitimate Old Timers, were always ready to talk on and on about some past swell.

It’s hard to compete with some epic swell story from some era one wasn’t part of. I certainly couldn’t; not stories with outsized characters and adventures. I always listened; the tales were always like myth, like magic; as if the coast was backed-up by Sherwood Forest and the Emerald City. Legends.

One of those older characters, Gingerbread Fred to his friends, no shirt under a well-worn v neck sweater, who claimed to have surfed Tijuana Sloughs and Killer Dana and Mysto Breaks outside Windansea (verified, I was told, by ‘one of the Holders’), was selected for the on-air interview.

“I just saw the flame, man; it was so, um, uh, intense. You know?” His hands seemed outsized, moving around the same way they did when he talked surf. “Bright. You know? I thought I’d heard something, over by the…(both hands, all his fingers pointing) compound. I like to, you know, walk on the beach. There was just a sliver of moon. I was coming up the stairs when I seen it. The flames. A car was pulling away. No lights. It didn’t squeal out. Just…”

His hands were out now out at his sides, palms out, a gesture, I thought, of surrender. “I ran, but… I don’t run. Used to. Thought maybe, you know, I could help.” The camera and the light moved in too close to Fred’s creased face. “It was like, um, the second coming; maybe; But then… then I could smell the gasoline. Chulo. Good surfer. One time…”

The camera switched, abruptly, to the reporter. “Well,” he said, “we will continue to…”

He continued. Two guys and a woman from the white “Jesus Is Lord (converted school) bus” that seemed to always be parked around Encinitas walked past him.

I was pretty sure I saw Ginny Cole in with a couple of the San Dieguito High School crowd, but the pan of the crowd passed too quickly. No rewind.

TWO DAYS LATER- THE OPTIMUM VIEW

The walls were back to white when I next went to Swamis, against my mother’s warnings, two days later. It was a Saturday. Weekend. Barely light. I got there early enough to park the dust bowl tan Falcon station wagon in the choicest spot; a little toward the stairs, but front row, and offering the optimum view of the lineup. It was the same car my Mom had used to drive us to swimming lessons and church and Doctor visits, and to the beach; surf mats and Styrofoam surfies and whining siblings; the Aloha racks now pretty much rusted in place.

A predicted swell hadn’t materialized, a south wind was blowing. Maybe it would clean up, even get bigger.

So, I would wait. Waiting is as important a part of surfing as trying to be in the water before the best conditions hit. My shift didn’t start until ten-thirty; about the time the onshores get going. Perfect. I could wait. I had my notebook, college-ruled; I had the probably-stolen (not by me) four track tape player under the passenger’s side of the seat; and I could do some writing.

Still, I really wanted to sneak over to the crime scene, the thick, high, stucco-finished walls, gold flower bulbs perched above them. There was (and is) a wrought-iron gate in the higher, arched entrance, also topped with the flower (though it could as easily be a flame, not dissimilar to the top of the statue of liberty). This is not the actual entrance to the Self-Realization compound, a place where people go seeking enlightenment, a realization of the true self.

So, I did walk over. I expected more. I expected some explanation. Other than some obviously-new asphalt, some new soil around newly-transplanted, but full-sized plants, it looked… it looked the same as it always had; as it did even in the late 1950s. Exactly the same.

There were cigarette butts, quite a few of them, forming a half circle, a perimeter. No one had bothered to clean up outside the police line. I positioned myself dead center, optimum view, pulled the pack (box, not soft pack) from my windbreaker’s pocket, pack of matches inside, lit up a Marlboro.

“Power of suggestion,” I said to myself, throwing the now-empty pack of matches down with the line of butts. “Peer pressure.”

There was an opened pack of matches on the ground. Half the matches were gone, removed left to right. “Left-handed,” I thought. I picked the pack up, tried one of the matches. Nope, too soggy. Rather hip lettering on the cover read, “Carlsbad Tavern.”

Yes, I did think it might be a clue; one missed clue. Important. I knew the place. That is, I knew of it. I put the pack inside the Marlboro box, that in the windbreaker’s inside chest pocket. Maybe they’d dry out.

……………………………..SINNERS LOVE COMPANY

When I approached the bluff, surfers I knew well enough to give or return a half-nod, four of five guys, and one girl, Ginny Cole (you always knew the names of the few girl surfers), were sitting on the guard rail, or standing in front of it on the bluff, directly in front of my car. Close. Optimum view. Ginny and one of the guys, who had been watching me, evidently, turned back around after I gave a bit of a gesture that I meant to say, “Yeah, I looked; so what?”

Ginny pulled her coat and an over-sized gray bag (I would say purse, but surfer girls were way too cool for that) off the hood of my car. Not in an apologetic way. Two of the guys continued to lean the just-past-comfortable distance between the railing and my car.

Fine. I probably would have been sitting on the hood if they weren’t there. Casually. Observing.

Each surfer had a small carton of orange juice or a quart of chocolate milk in their hands; maybe a cold piece of pizza. One might have had a large coffee from the 7-11 down toward Cardiff. One very well could have had a mason jar of juice, carrot always an ingredient, some color from sick green to sick orange; always willing to share. Not with me. Maybe once.

None of them were smoking. These weren’t my high school friends, so anxious to learn how to smoke; starting out with, Parliaments, maybe, moving on to Marlboros or Winstons, arguing about which was better; urging me to be cool, to not be a pussy. Tobacco evangelists.

Sinners love company, I had thought, and I put off starting the very same habit my father had only participated in in secret; or at work, away from his children.

Carlsbad Tavern.

Still, we knew. Camel non-filters. My mother kept his last half pack in a dresser drawer with his badge. Occasionally she would open the drawer.

I squeezed the cherry out, tossed the butt through the opened driver’s side window and onto the floorboards, grabbed my fairly-full quart of chocolate milk and my half-gone package of donettes off the seat, went into a practiced lean, a slouch, against the backseat door.

Frosted, never chocolate.

……………………………DOWNRAIL SPEED MACHINES

It seems wrong to me, now; it’s obviously wrong; but, somehow, when I was a teenager, it seemed all surfers were somewhere around my age. Some younger kooks, some older surfers. Not many of those; or maybe I just didn’t focus on them; only the ones who were well known, who had been in “Surfer” magazine. If they showed up, their names spread quickly through a parking lot or lineup: L.J. Richards, Mike Doyle, Rusty Miller; surfers you would, definitely, keep track of; just to see if they were all that good. Better. Were they better?

How much better?

But these were days of evolution in surfing; shorter boards, more radical moves, backyard soul shapers, V bottoms and downrail speed machines; and the new heroes were younger; more like my age; s-turns and tube stalls and 180 cutbacks.

The first 180 cutback, with an off-the-foam to bottom-turn I ever saw was at Swamis, from halfway up the stairs, performed by Billy Hamilton, on a longboard; smooth and stylish. He is older, maybe even ten years older. Still, older.

Chulo Lopez was in this group. Aggressive, stylish, and dominating. He had once, on a glassy evening at Pipes, given me the signal to go on the first wave of a set. Two other surfers in position to go didn’t go. I had to.

……………………………………SECOND TIER

“Chulo,” someone said, his waxed-cardboard milk carton in the air. There was a sort of muffled chorus, “Chulo,” from the surfers on the guardrail.

“They’re saying it’s some sort of… cult thing.” “Maybe it’s kinda like… you know, those monks burning themselves up over in Vietnam.” “No; dork; that was… political.” “Did you see it? I mean, the… the burn marks. It was, shit, there were…” “The smell.” “barbeque.” “Ohhh; ick.” “All the cops. Highway Patrol, Sheriff’s deputies… detectives.” “Yeah.” “One of them asked me about Jesus Freaks.” “What? No.”

One of the guys had looked at me when someone said “deputies,” elbowing the guy next to him. “Oh,” I thought, “so someone knows who I am.”

“Drugs.” That was a statement. Though it was made in the direction of the water, it was meant for the surfers on the rail, and loud enough, grownup enough for the adjacent surfers, the second tier; me; a couple of other surfers who knew better than to get too close to the local crew. Not that any of us formed a second-tier crew. Maybe two guys came together, but, no, random loners- not in a cool-loner way.

“Drugs,” the older man, Wally, repeated; “One way or the other. Drugs.”

Wally was a kneeboarder. Even his kneeboard, yellowed, beat up, patched-up, was old. One of the teenagers on the rail, part of the crew he drove around at dawn, was, I found out much later, his son. Wally had walked from the direction of the green, wood outhouse (still there at that time) and the stairs (at two other stair systems since then), and had positioned himself, a bit offset, but between the bluff and the guardrail surfers. Having gotten everyone’s attention, he looked out at the water. Optimum view. as I said.

The guardrail crew reacted. “Maybe… I don’t think Chulo was even a stoner. Maybe…” “Chulo? No.” “Maybe he was a narc.” “Fuck you, man. Narc? Chulo?” “Hey, A-hole; either he was a stoner and the cops… I mean…” “Oh; so, like, if Chulo was a narc…””Chuck you, Farley; go back off in your own jackyard.” “Geez, man…”

“Narcs,” I said. Each person in the loose crowd, including Wally, looked at me before he (or she- the one girl, Ginny- remember?) looked in the direction I had nodded.

“Detectives,” I said, a little louder, hands at my mouth to (try to) focus my voice.

A big, American-made, unmarked police car; the ‘varmint lights,’ the plain hubcaps, and a “Del Mar Fair” decal on the back bumper were the clues; had driven past, on the other side of the mostly-empty double-row spots. The tail lights stayed on for a while after it was parked in the dead end of the lot. Both front doors opened. Detectives.

We had one of these Del Mar Fair stickers on the Falcon. Mark, one of my friends from school, and, more so, from the Boy Scouts; a sometime-surfer, pointed out this real-or-imagined detail of unmarked police cars. “Yeah,” I’d said, “My Dad put it on the wagon; it’s sort of a, um, like, ‘don’t pull me over’ kind of, uh, code.” This prompted several other friends to acquire and display similar decals.

The decal, faded, was still there. The one on the unmarked car was newer. Southern California Exposition. Yeah. It was always the Del Mar Fair to locals.

………………………………………………JUST SAY, “THANK YOU”

Two detectives, so obviously cops, approached. One was taller; tall, California Highway Patrol tall (they had height restrictions); the other huskier. Both had cop mustaches, no farther than the edges of their mouths; both had cop brushcuts; one had sideburns that probably hit the limit of the San Diego County Sherriff’s Office hair code; each one sported a colorful and wide tie to, I thought, offset their drab suits, to look hip. Hipper.

One of them stopped at the passenger side of my car, the other one came around the back and stopped at the driver’s door. Each was sort of smiling; though it was more a ‘don’t you move’ smile.

Oh. I was the only surfer left.

The shorter detective opened the passenger side door, then looked at me, didn’t look inside, but, instead, checked out the looked up and around and out. The sun shone only on the horizon; the south wind had calmed. “Nice view,” he said. “Optimum,” I said.

Two surfers, of the too many crowded into Wally’s old car, boards and a kneeboard piled on top, flashed the peace sign as they passed me. One of them pointed forward. I knew all the locals were laughing. I returned the peace sign, turned toward the taller detective, and threw my hands onto the roof of the car.

The tall detective smiled, waved off my over-reaction. He opened my driver’s side door, looked at the 4 Track tapes scattered on the seat, looked for the player. Not installed under the dashboard. The shorter detective pulled it from beneath the seat on the passenger side, looked at the tangle of after-market wiring. Oh. Stolen. He set the player and my notebook on the roof, on top of my latest backyard stripped-down-and-reshaped surfboard. Rude, crude, badly-glassed.

“We’re just asking a few questions,” he said. “Got a license?” I pulled my billfold out of my back pocket, stuck the license toward him.

The two detectives and I looked around at the same time, moments after the one syllable ‘whoop’ of a police siren.

Three Sheriff’s vehicles and a Highway Patrol car, lights on, blocked the entrance to the lot, the exit to 101. Wally’s car hadn’t quite escaped.

“Oh,” the taller detective said, holding my license close to my face, then leaning down and closer; “hadn’t seen you in a while. The, um, funeral; maybe.”

No. I hadn’t looked at any faces there. There had been other occasions, softball games and picnics. He would have been half-drunk, at least; and never able to beat my dad at… anything; and my father was not a gracious winner.

“Wendall,” I said. I took the pack of Marlboros from my windbreaker, pulled a cigarette out, took the ‘Carlsbad Tavern’ pack of matches out, looked at the logo, at the two detectives; opened the pack, red stains against the back of the cover. “Too wet,” I said. Detective Wendall stuck a cigarette in his mouth, lit mine with a San Diego County Sherriff’s Department-logoed zippo. “Swindling Wendall,” I said, with a smile.

“Swindling Wendall” the other detective, with a laugh and a hit to his partner’s shoulder, said.

“Dickety-Dick Dickson,” I said, putting the wet matches back into the windbreaker, checking the group standing almost casually outside Wally’s car. There was the back of the very-tall (of course) Highway Patrolman, Wally, four teenage boys, with Ginny Cole in the middle. They were all looking at me and Wendall and Dickson, and I was thinking only about how much I looked like a fucking narc.

It was too close and too fast to focus. I doubled-over, Wendall’s fist still in my stomach. The cigarette popped out of my mouth, onto his shoulder. Dickson brushed it off, Wendall’s fist now a hand on my shoulder. I stood up straight. This was necessary, this was mandatory.

“Just say ‘thank you,’ Jody.”

Dickson stuck the cigarette back in my mouth. “Thank you.”

JUNE 20th– BEANERS

It was mid-afternoon, early in my shift; and I was bagging groceries for a particularly talkative woman; somewhat older than my mother, dressed in a house dress, some sort of white scarf thing on her head, curlers bulging in some sort of random alignment under it. So, since women my mom’s age tried to look younger, hipper; this woman was, yes, older.

“Durn Texans,” she said, “worst kind of tourists.” She was talking more to the similarly-aged checker, Doris; Doris nodding politely. It was more than halfway through Doris’s shift and some of her willingness to chit-chat enthusiastically had worn off. “Surfers,” the patron said, kind of looking at me. “Surfers from… Texas? Texas. What do you think… (looking at the name tag on my apron) Jody? Jody?”

“Jody?” I mouthed, looking at the nametag on my bright green apron; acting as if it wasn’t my name. It wasn’t. I’d been looking for another, better nickname for years. Jody was my father’s joke. Jody.

“Jody’s got your girlfriend,” my father would say, drill instructor voice pop-pop-popping the cadence. “One-two, one-two, one-two-three-four… one-two…three-four.” Jody.

I shrugged. I did notice the woman had some sort of east coast accent; northeast, not that I could discern Philadelphia from New Jersey from anywhere else; but she hadn’t lost the European edge, that inflection; rhythm, maybe.

She pulled several items out of the bag I had, probably, overloaded. “I would rather make more trips, Jody. If I had big muscles, like you…” She smiled. I opened another bag. She put her heavy purse on the counter. “And they all have money. They want to rent by the week. They get sand in the shower; make a mess. Drink.” She looked from me to Doris, now looking for the price on a dented can of string beans. “One threw up on the sidewalk. Awful.” Back to me. “And… and they chase around our young girls. Believe me…”

I was distracted, not sufficiently interested. I did nod, but the woman checked me out for another moment; Jody, in the apron, my hair not long enough to pull back (but parted in the middle), my mustache more like peach fuzz; and she turned back toward Doris. “Believe me, Doris, if I didn’t charge them extra, I’d never…” She kept talking; I continued bagging, but I wasn’t listening.

Jumper Hayes, over by the big front windows, was talking to Tony, the shift manager. They, obviously, knew each other. I guessed this might be the first time they’d seen each other since Jumper’s return; each with a hand on the other man’s shoulder; laughing at… laughing at things that weren’t really funny.

Jumper pulled up the left sleeve of his t shirt, poked at a scar on his bicep with his right hand, laughed. Tony started to roll up his right pant leg, stopped, sort of grabbed at it, kicked it out to show it still worked. They both looked over at two young men, in clothing appropriate for working in hothouses (though more than I would have worn in that wet heat), standing, obviously nervous, closer to the big bags of dog food, fertilizer, and charcoal, each with a check in his hand.

“Wetbacks,” the woman said. “Beaners,” she added, in case I hadn’t gotten it. I put her ice cream in a white, insulated paper bag, placed it in with her TV dinners. “Guess they can’t just go to the bank like regular folks, and…”

Tony, an older man with a bow tie and one side of his shirt untucked, did his sort of half-limp walk over to another register, opened it with the key on his belt. The two workers, on a signal from him, backed up by one from Jumper, approached. Jumper handed one a pen, pointed to the back of the check.

“Y’all need some help out with that, Ma’am?” It was the closest I could come to a Texas accent.

A woman with two children, one in the cart, her free arm holding the older child’s right arm pretty much straight up; approached the other register. She looked at the two men taking their cash. Each turned toward Jumper for a moment, folding and pocketing the bills, on his signal, before stepping away. She looked at the manager. She looked concerned. She looked at Jumper.

Jumper stuck his hand out. Tony took it, put his other hand on Jumper’s shoulder.

Jumper smiled at the child in the cart, smiled at the kid not yet released from his mother’s grasp. He nodded at the manager and smiled at the woman. She smiled back, let go of the bratty child, who, immediately, grabbed a candy bar from a nearby rack, stuck it, wrapper and all, in his mouth.

The woman pushed her cart toward the other exit, clutching the strap of her purse, her receipt, and her green stamps in one hand.

JUNE 22- CHUBASCO

I was taking one last look from the bluff at Grandview, trunks and towel over my board; just in case the waves were not what they sounded like in the dark. It had to be surf from some distant storm, some chubasco in Baja, or… I didn’t really know; I had heard some waves come from as far away as New Zealand. Travelling. Hitting islands, wrapping around headlands; peeling; like the images from the magazines; perfect, a slideshow in my mind.

This wasn’t perfect; storm waves overwhelming a beachbreak. Maybe I would try Swamis; or Cardiff Reef.

“Bagboy.” He may have said it more than once. “Bagboy; it’s closed-out.” I didn’t respond. “Fallbrook.”

“What?” I turned to my right.

Jumper stepped around, from my left, and was almost in front of me, “Fallbrook. Bagboy. You.”

“Don’t live in Fallbrook anymore. After graduation, we…” He cut me off with a swipe of a hand.

“So, not a valley cowboy; huh?” He bowed his legs in a sort of stage cowboy movement.

“Never was.”

“But you did live in Fallbrook. Right?” I nodded. “So, your daddy knew enough to not live where he worked.” I probably looked suspicious. I was, of anyone who mentioned my father. Apprehensive would be more accurate. “Wanted to keep his family safe; away from… from his work. Don’t blame him.” I didn’t have time to respond. ”You going out?”

“I, um… it’s pretty, uh, big. Maybe it…” I stopped myself, looked over at the waves; broken lines, ugly green-gray, no discernible peak, closing out. “You?”

“Hey, Fallbrook; I will if you do.”

“Really?” I may have been a little too thrilled by this statement.

“Fuck no, bagboy; it’s fuckin’ closed out. There’s no glory in surfing this shit.”

“I guess not.”

“Swamis, now…” He waited a second. I tried to nod slowly, like I hadn’t already thought of it, tried not jump up and down or break into a run. ”Swamis… should be fun.”

Jumper turned, walked away. I followed. He turned around, walking backward, about halfway to the street, at the place where I could go down the washout or back to my car. “Should be,” I said, breaking into a run as I passed him.

FEBRUARY 1969- DEVIL DOGS

I probably could explain why I started writing about Virginia Cole before I wrote about this incident. Easily. I noticed it the third or fourth time I went over this chapter, editing, re-re-re-editing. Rather than rewriting, I’ll leave it the way I originally wrote it. Our memory is a sort of self-editor; saving important or meaningful things, allowing the peripherals and tangents to drop away.

Ginny Cole was, to my seventeen-year old self, perfect. Maybe some of the girls I’d gone all through school with were great, but, yes, I’d gone all through school with most of them. Yes, there were, because Fallbrook was on the east side of the triangle that is Camp Pendleton, new girls, daughters of Marines, who would come into the school, three years here and gone; there were daughters of Civil Servants, daughters of pharmacists and ranchers and irrigation contractors and builders, but Ginny Cole was… she was miles away from dusty Fallbrook. Mysterious, exotic, distant; and she surfed. She would understand that, what that means; surfing. Perfect.

………………………………..Images

Ginny Cole was like the best photos from surfing magazines; like my best rides. I could bring her image into my mind at will; images from the few times I’d been on the beach or in a parking area or in the water with her. Not with her, around her. It’s not like she knew me; another teenage surfer, awkward out of the water, not skilled enough to be noticed in the water.

Except that, she was a girl. She would be noticed.

Ginny wasn’t the only girl surfer in the North County; there were others; but she was serious, she was good. A couple of girls were better surfers. I had seen Barbie Barron, Margo Godfrey… Barbie in the water and in the parking lot at Oceanside’s shorter jetty; Margo with Cheer Critchlow at Swamis on a day that was uncrowded, big and nearly blownout; both just casually walking out, chatting; paddling for the outside peak. My two friends and I shoulder-hopped, choosing only the smaller waves on the inside.

Coolness, casualness, some sort of self-confidence, some sense of comfort in one’s own skin.

Things I lacked, things I appreciated.

The days were just getting long enough to make it from Fallbrook to the beach before dark. My 9’6” Surfboards Hawaii pintail was on one side, last of the longboards of my youth was on one side of the rack on (sometimes called Dipshit Dave) Dave’s VW Super Bug, his pre-graduation gift. I think his newer-but-stock Hansen was on the other side. Dave had picked me up as I raced from my last class. He floored-it across the Bonsall bridge, despite an overlarge truck coming the other way, chose going through Vista rather than toward Oceanside. “Faster,” he said.

“Faster, then,” I said.

We were just coming down the ramp at Beacons when Ginny and another girl (no, I didn’t know or don’t remember her name) were coming up, boards under their arms, colorful towels over the boards; side by side; laughing. Ginny’s canvas purse/bag was hanging on one shoulder. The stainless steel turnbuckle closure on Ginny’s shortjohn wetsuit was disconnected, unsnapped.

There was skin showing. Freckles on her shoulder. I was 17. Ginny was perfect, and she might just look at me as we passed. I gave Dave a hip check, my only basketball move, pushing him toward the scrub and iceplant on the hillside.

“Virgin-e-ya,” a voice from behind her said; “Virgin-eee-yaaa.”

If I said everything stopped, it would be an exaggeration. But it did. I stopped.

And Virginia Cole did look at me. She blinked. She and the other girl lowered their heads, their smiles gone. They passed Dave and me single file, Ginny in front.

There were three guys, in street/school clothes, clunky polished shoes; high school age, at the bottom of the ramp; kind of congratulating each other. They weren’t surfers. Jerks. The guy who had made the remark was in the lead, crushing and tossing his empty beer can into the brush as they headed up. Jerk Two, half a six pack of Coors held/balanced on his chest, handed Jerk One another.

Dave shook his head, tried to step in front of me. He wasn’t fast enough, convincing enough. At the halfway point of the path, at the curve, I blocked them with my board, held sideways at my chest.

“What?” It was the lead guy; maybe a bit flushed; his smile changing to a sneer. Maybe not quite a sneer; just one of those ready-for-confrontation looks.

“Nothing, A-hole; just thought you might want to rest a second.”

“Fuck you.” The front guy, and I probably should give a more complete description of him and his high school-aged buddies, both adding their backup “fuck you;” but I won’t. He was just another high school Jerk, the acne on his cheeks a little redder than usual, probably, from the exertion of trying to walk in soft sand in leather wingtips, from the climb.

“You were a little disrespectful. Don’t you think; Jerk?”

Jerk’s crew and Dave looked up at the top of the bluff. Evidently Ginny and her friend were looking down. Jerk and I had to keep looking at each other.

“Ginny… Ginny Cole? Ginny Coldddd? She’s a stuck-up fuckin’…”

……………………………………………ALMOST-NUCLEAR

I’m trying to go through the words a teenage jerk would give for a girl in 1969. It would have been stronger than bitch, but certainly not cunt; that would be nuclear. Twat was almost-nuclear. Not so much a west coast term.

Somewhere in the previous school year, rained-out, my P.E. class had to go into the gym. The girls were playing volleyball in their unflattering red outfits, rather like overalls with the arms and legs shortened; and the boys, in our white t shirts and unflattering red shorts (though cool guys always tried to get away with wearing boxers underneath, hanging out just enough), were hanging by the front doors. We knew enough not to make rude (and loud) comments, but some new guy from the East Coast made some disparaging remark using the term, ‘Broad.’ How dare he call our ‘chicks’ ‘broads.’ Several (other) guys had wanted to give him a swift punch to the kidneys. No one (including the east coast kid himself) would say who did.

I dropped my board. Jerk and his friends, and Dave looked at it, fin up.

Hitting someone in the face is nuclear. The shoulder, maybe; was acceptable. “Harder!” “That all you’ve got?” Push, push back, a few glancing blows and a tie up; this was suburban teenage fighting. And, as Jerk pulled his right arm back, I hit him with a straight shot that instantly bloodied his nose and lip.

It wasn’t full speed. I had held back.

The other two guys were, obviously, trying to decide between fight and flight. Everything stopped. Again. I looked at my hand. Jerk put his left hand to his face, looked at the blood. The other two guys looked at the blood on his face and hand, stepped away from their friend.

“Devil Dogs,” Dave said to the friends, his biggest smile on his (slightly-pimpled, had to add this) face; “Joe’s a fuckin’ Devil Dog.”

I picked up my board. There were several drops of blood on it. I wasn’t sure if I was thrilled or sorry. Not enough of either.

“It’s just… um… you were rude.” Jerk looked like he might apologize; or, worse, cry. “Hey,” I said, taking Dave’s towel off his board, handing it to Jerk. “My dad made me go. It’s really… it’s Devil Pups. Marines. Didn’t want to go.” I stood aside, opening the ramp. “We’re going to go surfing now.” I took the towel back, handed it to Dave. He took it with a shrug. “Just, um; you’re okay, huh?”

Jerk nodded. We walked on.

“Hope he doesn’t cry,” Dave said. “Your dad would’ve… I mean; if you ever even started to…” As we reached the sand, the sun way too close to the horizon, Dave ran next to me, looked closely at my face.

I wasn’t crying, quite, but I was not thrilled. I wasn’t sorry. I’m pretty sure I smiled, maybe even laughed. “Devil Dogs!” I ran for the water, didn’t look back at the bluff until I was knee-deep. The sun bounced back at me off windows, car windows, house windows. Silhouettes. Maybe one of them was Ginny, I thought. Maybe I was wrong.

Dave caught a wave before I did.

JULY 20TH– MAN ON THE MOON

This was the day a man first walked on the moon. I had surfed. Somewhere; maybe Stone Steps; trying to find a little peak in the peak of Summer; summer and all that meant in a Southern California beach town recently isolated by the completion of I-5.

There was talk, at that time, of the North County beach towns (Leucadia, Encinitas, Cardiff-by-the-Sea, Del Mar) suffering when 101 was no longer the main coastal north-south route. Whether they did or didn’t depends on your interpretation of ‘suffering.’

In the still images and video (and, actually, film) clips that are stored in my memory, there was (though I may have imagined it there) a TV in the front of the classroom, black and white only, set on an AV cart, tuned to the non-stop coverage of the moon landing.

A Woman entered, looked at the fifteen or so grownups and almost-grownups scattered around the classroom, each with a stack of papers on individual desks that were exactly like the ones at Fallbrook High, and probably Vista, San Marcos, Escondido, Orange Glen, San Dieguito (those same beach towns); the districts that fed into the Palomar Junior College District. She looked at one of the papers in her left hand, erased “Biology 101” from the chalk board.

“Now,” she said, “now;” speaking louder when no one looked up after the first ‘now.’ “You people are right at the line; the cut off. Your choices… (louder) are limited. You may not get all the classes you want.”

Creative Writing; yes. And I wanted English 101. Yes, I had tested high enough to skip the remedial, non-credit English; I wanted… Art; yes, definitely. Basic Drawing. Two classes still open. 8am. Of course; too early for real artists. Monday, Wednesday. Okay. Being under eighteen (the cutoff might have been twenty-one at that time), I was required to take a Physical Education class. Fall Sports was closed. Badmitton. Really? Closed. Shit. Weight Training. Still open. No. Fuck. Okay.

Okay. A-okay.

I was pretty pleased, partly because I was there; here; signing up for ‘high school with ashtrays,’ junior college; college nonetheless. I was still writing, erasing, writing when Jumper Hayes entered the room, gave the Admissions Woman a big smile, which she seemed to appreciate, pointed toward the empty seat next to me with his rolled-up papers, and sat next to me. He scooted (noisily) his desk unit closer; like he wanted to cheat off me.

“Bagboy,” he whispered.

I scooted my desk away. Jumper followed.

The Admissions Woman looked around at the noise, but, again, only returned what I had to believe was another reassuring smile from Jumper. I feel compelled to mention that the Admissions Woman was probably about twenty-something, something under 25, and was, despite her pulled-back hair and Summery-patterned dress (no sleeves, no hose, tanned legs- I noticed, and no shoes) trying to seem a bit more professional, even stern, than she was able to quite pull off. She was rather like a substitute teacher in a room of recent high school graduates, professional students, draft dodgers, returning veterans.

“No shoes,” I thought, looking down at my huarache sandals. With socks. That wouldn’t happen again. No dress code here.

“Bagboy,” Jumper said; “I thought you were going to some big time University. Word is, what I heard is… you’re a brain.”

“No.”

“No? Okay. Maybe not.”

“I was… upstate… inland; not my idea; but…” I’m sure I smiled, despite myself. “Brain? Who would…?”

“One of those Avocado-lovin’, guacamole dip…dipshits; Bucky Davis, maybe; John Amsterdam; why would I remember? I’m not a brain…I’m not like you.”

Admissions Woman, taking a handful of papers from an older man; probably forty, at the door; scratched Philosophy II and Beginning Photography from the chalkboard.

“Shit.”

“Philosophy II?”

“No, beginning photography.”

“Oh. Sure. And, incidentally, Amsterdam still hates you. Brand new Dewey Weber performer.” He shook his head, moved his hands to illustrate a board crashing on another board. “Got to hang on to your board, Bagger.” He paused. “You prefer Bagboy… or Bagger? Bagger sounds a little more…” He nodded, nearly winked. “Or Jody?”

“That… Amsterdam’s board; wasn’t me. Different Fallbrook punk, man. Jody, that was my dad’s joke.”

“Yeah. Sure. And Tony, at the market; he’s in on it.” He was nodding; I nodded.

“They were both in the Corps. Not that they knew each other then; Tony was only in Korea; but…”

“As was I. In the Corps. Not Korea. Or is it ‘As I was?’” Jumper saluted; quickly, crisply; properly. He looked over at my papers. “Different wars, man. You takin’ any English classes, um, neighbor?” When I looked back, he went back to nodding. “Wrong side of 101. Too bad. You probably have to go five blocks to get across, but… guess you’re a Leucadian. As far as I know, you and I; maybe… (he moved his hands back and forth in a balancing motion) Carson Holder; we’re probably the closest things to Grandview locals.” I blinked “So, well…”

When I determined nothing was following ‘well,’ I said, “beats living in Frog-butt; huh?”

Jumper laughed, looked at the woman from admissions, gave her another, bigger smile, kept it when he looked back at me. “So, guess you don’t have the horse anymore.” He let that hang for the moment it took for me to look around. “Any longer? No longer have the horse?”

He didn’t drop the smile. I’d love to think I didn’t seem surprised. Or rattled. “No, we… the horse…” I restacked my papers, whispered, “Fuck you, Jumper;” scooted my desk away, again, a bit more noisily than I might have preferred. Jumper was still smiling.

“Oh. Sure; and the horse I rode in on.”

……………………………………………………EASY A

Jumper stood up, his desk unit like a skirt, walked closer to me. He slid his preliminary class schedule in front of me, pointed to Criminal Justice; pointed to the same title on my schedule. “I am going on Uncle Sam, though; G.I. Bill. Semper Fi, (whispered) motherfucker. Full ride, man.”

“It’s California… Man; free education. And, besides; I’m not interested in…”

“Easy A, Jody; and… (back to a whisper) Military; cops; it’s a family tradition. Isn’t it?”

I crumpled up the first and second versions of my schedule in my right hand, stuck my middle finger out and a little too close to Jumper’s face. Surprised at how instant my anger had been, how it was staying at that level, and how Jumper’s reaction continued to be a smile (“Insolence,” my father would have said); I pulled my hand back almost immediately, flattened-out what had been a fist, and slapped my hand on the papers to the desktop.

“If my father… I’m… everyone knows who my father was. If I…” I looked at my form. “I’m done, June, Juni, Junipero… Mr. Hayes. Fifteen units. Full load. Done.” I stood up, picked up and straightened the other pages. “I’m not interested in being a…” I lowered my voice, looked around the room. No one was looking up from their papers. “…Fucking cop.”

“Marine Corps, then. Huh?”

The Woman erased Psychology 101 from the board just before I got to her. I looked at my form, I looked at Jumper Hayes. He still had the same smile, mouthing, “Easy A;” stepped in front of me, very close to the Admissions Woman. “We’re both taking Criminal Justice, Miss… (looking at her name tag) Julianna Goldsworthy (stretching out each syllable).” He stepped back, went into a sort of superhero pose. “Do I look like a cop, Julianna?”

She seemed too, maybe, bedazzled to respond with more than a nod. And a smile; a smile she dropped when she turned toward me. “Family tradition,” I said, “Easy A.”

Jumper looked at me, looked at Julianna, at the TV, back at Julianna; “Big deal, huh; man on the moon and all?”

Julianna looked back at Jumper. Her smile, half as big as it had been, returned; but the nod seemed twice as enthusiastic. She almost giggled. “Soooo cool. The moon! Historically (lowering her voice) fucking cool.”

“Uh huh,” Jumper said, sharing her little ‘oops’ expression. He stuck a fist out, shook it, said, “To the moon, Alice.” We three, and a couple of others listening-in, of course, got the illusion.

Jumper looked at me, me maintain a serious expression, turned back to Julianna Goldsworthy, motioned her a bit closer. “I want to find out who killed Chulo Lopez. Mr. Joseph DeFreines, Junior, here… DeFreines is a fancy to say ‘French,’ you can call him Jody… probably; he wants to find out who really killed his father.”

SEPTEMBER 10- IN A DIFFERENT LIGHT

It wasn’t actually dark, just that empty, colorless sky, sunset shades fading. I was walking fast, then running on the sidewalks, past the blocks of classrooms, most unlit; a camera strap around one wrist, piece of paper in the other hand. “Should have scoped this out,” I said, probably out loud.

There were mostly older men in the first classroom with lights on and a door open. White-haired and conservatively dressed. “Photography Two?” “No, kid; real estate.” Laughs, two guys pointing to the next building over.

Everyone in the correct classroom seemed to know each other; standing around in small groups, some in those multi-pocketed news photographer coats; versions, I thought, of great white hunter jackets. I looked down at my favorite vinyl windbreaker, selected because it had big pockets, pockets being an important part, evidently, of being or looking like a photographer.

Most of the Photography II folks were men; not as old as the potential realtors; but, I couldn’t help thinking, probably mostly interested in artistic nude photography. Artistic. Nude.

Then there was Ginny Cole; hair pulled back, a pretty-neutral-colored and oversized sweater and Levis, that large, gray-and-stained, possibly-canvas bag on the desk in front of her, waiting for some one to start the class; that Ginny Cold look on her face.

Not that I knew her.

I did know the look; the don’t-even-think-about-it expression probably necessary for a girl’s survival in the surfing community. Or any community.

Still, I sat in the desk next to her. She didn’t look around.

“It’s like a pervert convention,” I said. No response.

“The trenchcoats.” Pause. No response. I chuckled, scanning the room again. Virginia didn’t. “I surfed Pipes this morning… pretty good; came here from work (all the while I’m probably nodding like a fool). Got a great deal on grapes.” Nothing. “Seedless.” I thought I saw a bit of a smile, quickly dropped. “You get any waves?” No response. “They’re seedless; on sale.”

Virginia Cole turned, possibly just to make me stop talking. This time she had the ‘drop-dead-and-die’ look ready to go; possibly even moving to the ‘may-your-dick-fall-off-before-you-drop-dead-and-then-die’ look; but, just as she turned, as can happen in the hours after a person surfs, a stream of water poured out of Ginny’s nostrils. She quickly brought a hand up to stop it.

She looked at her hand, looked at the puddle on the desk, looked at me. I don’t know if I was smiling. Sure, had to have been.

Her expression was almost a smile. “Seedless, huh?” It was a smile.

“Okay, class;” a voice from the front of the room announced, “time to pick a partner for the dark room.”

I took the neckerchief I had around my neck (part of my junior college-cool outfit), handed it to Ginny. She looked at it for a second, unraveled it, wiped her nose, eyes on me. Then she reset her polite-but-serious face.

Yeah; but, raising the Yashica camera my mom had bought from a Vietnam veteran at her work, a man dying of some unspecified disease (“So young,” she’d said; “Fifty bucks” my dad responded, to her, “Better than that Brownie” he said, handing it to me). I considered pointing the camera toward Ginny, almost wanting to see her ‘drop dead’ expression. Though I never took the shot, that’s still my top Ginny Cole image.

Something about a woman in a dark room; the lighting so different; highlights and profiles, a certain intimacy. Maybe I was a little too thrilled. This wasn’t a date.

I was worthless. When it was obvious I didn’t know how to do anything, she took my roll of film, got it into the tray of developer. “How did you get in this class?”

“Beginning photography was full.” I just stood by. Soon, the first roll of film I would ever (watch/assist) develop was in the fixer. I had to piss. Desperately. I couldn’t leave. “You?”

“Me? What?” I tried to pass on what I meant with a shaking of the hands. “Me. Took it while I was in high school. It’s… possible. It’s allowed. Quit dancing.”

She looked at my feet. “No shoes?” I looked at her feet. Tan, brushed leather almost-hiking boots. “Shoes. Shoes. Good.”

I grabbed my roll from the tray, by the edges, held it up to the reddish lights; negatives, 35 millimeter white and black images of waves, of people, strangers, in the parking lot at Swamis; of Erwin and Phillip and Ray, my closest high school surfing friends, from the last time we all surfed together; Swamis beachbreak.

Ginny took the roll from me, hung it on the line with her five rolls of negatives; flowers and iceplant and palm trees and sunsets and clouds and various members of the San Dieguito surf crowd in the Swamis parking lot.

The professor approached. “He’s had to figure out… he will… you don’t belong,” she said. “You can leave for a minute. Just… just stop dancing. Please.” I couldn’t. “Go. We’ll make some contact prints.”

“Uh huh,” like I knew what that meant. I avoided eye contact with the professor, side-stepped him and one of the big jacket guys.

“Oh,” Ginny said, “and don’t think you’re, like, my hero… anything like that.”

I looked back. She was resetting her serious face as the professor approached her, but, for a second, maybe…maybe she seemed to be actually seeing me, almost smiling; but then, there’s something about darkroom lighting… a different light.

…………………………………………………………….NOT A HERO, NOT A NARC

When I returned, slipping through the ante-room and the blinds of heavy plastic, into the chemical smell and red-tinged darkness, past the professor and other students, Ginny Cole was examining the drying negatives; her five rolls, my one.

“Are you taking this class just to save money on developing?”

“No. Uh, maybe; partially. It’s more like…” She had one roll on the counter, on a towel, dobbing the top side. That’s the one I tried to look at. She pulled it up and away. Thirty-five millimeter negative images. I backed-off, threw my hands up in a ‘no contest’ gesture. “It’s just… it’s not that… it’s not secret.”

“Okay. Not secret. Private. Sure. Private.”

The ‘private’ thing was too much to put between two people in a darkroom who really didn’t know each other.

Ginny picked up and held the roll, by the edges, backlit. There was a shot of someone blocking the path at Beacons with a board. It was me. Oh.

“Oh,” I said.

“Telephoto lens,” she said. “You should get one.”

“Uh huh,” I said, checking the other shots, one a closeup of the Jerk looking up, blood (white on the acetate) on his nose and mouth.

“It’s not like you’re my hero or anything.”

“No,” I said. “Telephoto. Have to get one.” She handed my neckerchief back to me. I looked at it, looked at her. “Perfect,” I thought. “I’m not a narc,” I said.

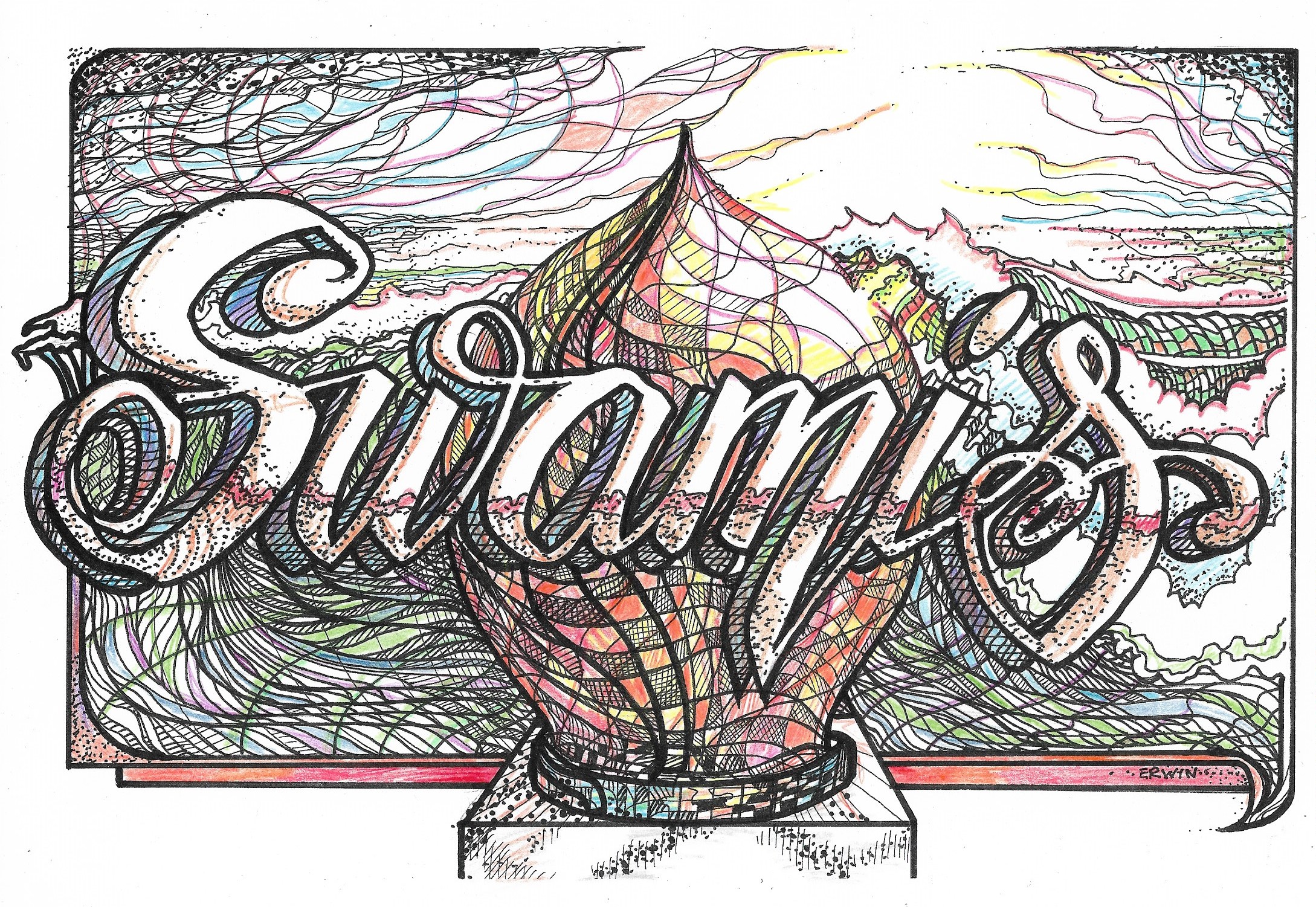

I got five copies of the original drawing, just so I could, maybe, take a few risks on the colors. This is the first attempt. MEANWHILE, I keep working on the story.

I got five copies of the original drawing, just so I could, maybe, take a few risks on the colors. This is the first attempt. MEANWHILE, I keep working on the story.