SO, JACOB WHYTE is the son of a cousin of JIM HAMILTON, a very interesting individual (timber-frame house builder/ski patrol/world traveler/more) who lives off Center (Road) and close to SURF ROUTE 101 in Quilcene. Jacob also has an interesting story. He has returned to Forks, Washington after an extended stay in California, Ventura area, during which he worked doing ding repair, most notably (to name droppers) for Channel Islands Surfboards, living frugally (growing his own food, that kind of thing), always, he says, planning to move back home to Washington State’s WEST END.

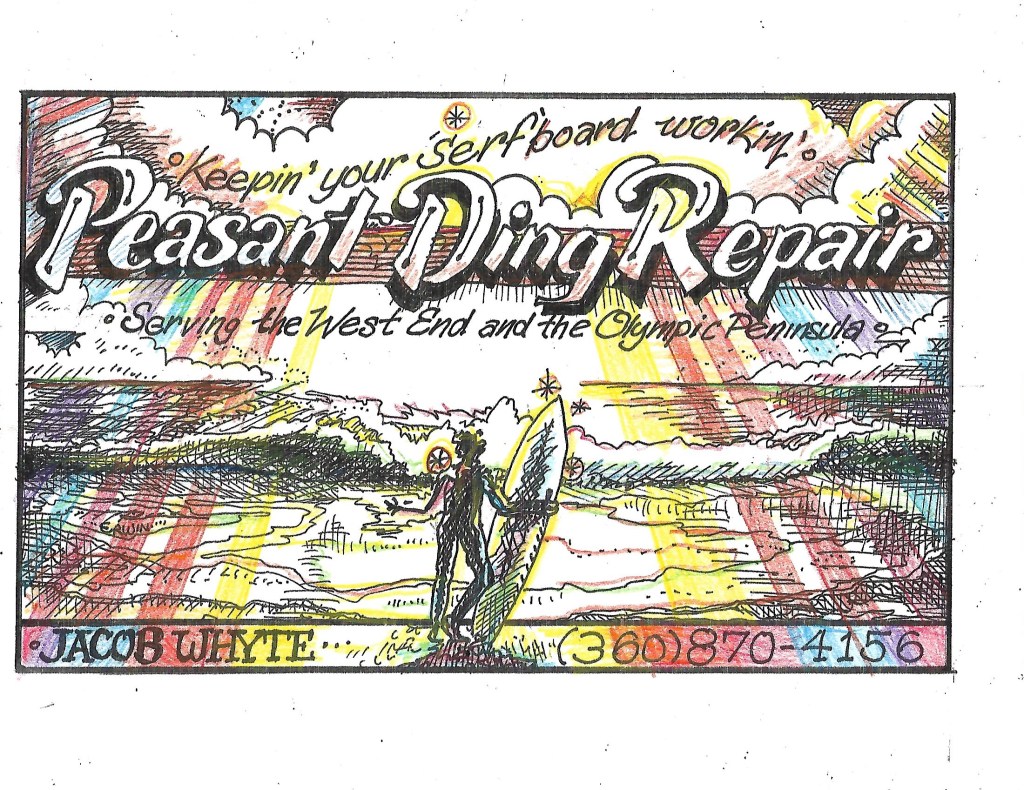

Now, the PEASANT thing: Jim, in asking (more like hiring/bribing) me to do some artsy stuff for Jacob, pondered the name. “Oh,” I must have said, “Maybe it’s like, you know, peasants, serfs, vassals, that kind of thing; I mean, like an allusion to… that.” “That would be… yeah, maybe that’s it.”

“It isn’t,” Jacob said when I actually got in phone contact, he at a far northwest secret surf location, me in the depths of a housing tract in East Bremerton. Didn’t matter, so much, I’d already done a drawing, black and white, printed a copy and colored it, either suitable as a flyer, or, reduced in size, a too-busy business card. “Yeah, Erwin, maybe the ‘serfboard’ thing is expecting too much of… surfers.” “Okay, how about the ‘serving the West End and the Olympic Peninsula’ part?” “Yeah. Sure.”

I ran a couple of other ideas past Jacob. Mostly about t-shirts; what would be appropriate, assuming surfers on the West End are not necessarily trying to invite more surfers over. I have ideas. LATER. It’s not like I can’t keep a secret.

IN MY CONTINUED attempts to produce a decent drawing of the fictional JULIA COLE, or, actually, a portrait of any woman, I came up with this. Attempts and failures. I should throw away the versions that got me to this one, possibly more useful to depict Julia’s mother, and stick this in some file with the other failed illustrations. BUT, wait, maybe if I just… Yeah, I have some ideas. ALWAYS. And I always want to get… better.

CHAPTER FOURTEEN- MONDAY, MARCH 31, 1969- PART FOUR

The two carpenters were carefully walking between the Karmann Ghia and the edge of the bank. Lee Anne turned toward them. “Joey, this is Monty, lead carpenter on the project.” Monty was sunburned, with a receding hairline and an almost orange Fu Manchu mustache. Early thirties.

Monty stepped in front of Lee Anne’s car, put a hand on the other man’s shoulder. Black, muscular, no older than eighteen or nineteen. “And this is…”

“Not a carpenter. Yet. Helper. Nickname… Digger.” Monty had only left room for his helper to stand on the very edge of the bank.

Lee Anne looked at Digger, shook her head, looked at Monty, and back at Digger. “No. Unacceptable. You have to… insist… on a different nickname.”

“Temporary,” Digger said. “Thought I’d be something like ‘Hammer.’ Nope. Got to earn your nickname ‘round here.” Digger slapped at a pair of gloves folded over his belt. He held out his hands, palms toward me, rubbed two fingers of his left hand across the palm of his right. He slapped his hands together. “Could’a been callin’ me ‘Blisters.’”

Lee Anne extended her right hand but didn’t accept Digger’s. “Blisters,” she said. “Not good, but… better.”

Monty gave Lee Anne a sideways nod and said, “Blisters, then.”

The younger carpenter had been rather boldly checking Lee Anne Ransom out. She looked him off with a quick widening of her eyes and a very stern expression. “Real name, please, for the record.”

Blisters backed up, put his hands out and up, his arms closer to his body. If he was impressed with Lee Anne’s response, he wasn’t apologizing. “Greg,” he said. “Or Gregory.”

“Gregory, then.” She turned back to Monty. “Or Greg?”

“Greg, then,” Monty said. He pointed to the parking lot. “We heard the cop car, didn’t see it ‘til it tried to turn in. It wasn’t the brakes. It was… the gravel. New, like b-bs; no way he wasn’t gonna slide.” He turned toward me before he added, “No way.”

…

The San Luis Rey Riverbed was probably half a mile wide. I had never seen the water more than a stream, a creek, even. The ground Monty and Gregory and Lee Anne and I were standing on was gravel and round river rock, with the usual scrub, some still green but rapidly fading grasses and weeds, and a few stunted trees. Taller trees in the center of the valley were mostly dead. Ghosts. Killed in the cycles of flood and drought. More likely flood. Drowned.

Monty pointed to the stump in the river bottom, probably fifty feet from the base of the fill. “The concrete had been poured. The leftover rebar should’ve been fuckin’ gone.” Though no one asked, he added. “Contractors. Separate. Not our job.”

Lee Anne said, “Separate. Not your job.” She attached a telephoto lens to her camera, aimed it at the road on the east side of the valley, focused it, snapped a photo, and handed the camera to me. “So, after your dad’s accident; the traffic was rerouted… over there. Correct?”

The lens was out of focus for my eyes. I twisted the ring at the base of the lens as Lee Anne had. “Correct.” I turned the camera past the carpenters and toward the journalist. Distorted. Out of focus. I snapped a photo. “Accident.”

Lee Anne took the camera and advanced the film.

…

Gregory and Monty and Lee Anne and I were standing next to the concrete box. There was a galvanized pipe in, another, perpendicular, out. Gregory, now gloved, had a shovel, upright, in his left hand. “You see, all the rebar got pushed out the way by the car… except for one piece. Jammed against the… stump.” He looked at me. “You get me?” I nodded. “They cut it. The… stump. Little later. Fire department.” I nodded. “Like a bullet, it was. Through the door and right through the guy. I seen him, right after. He was alive and all, like he was trying to pull the rebar out. No fuckin’ way.”

“My father… the guy.”

“Yeah.” The shovel handle fell against Gregory as he moved his hands into a prayer position and raised them to his eyes. “Sorry, man. No disrespect.”

Monty stepped between his helper and the stump. “We were trying to get it loose. No way. I’m smacking the stump with a framing hammer, trying to get the rebar loose. Or, even, pull it through the stump. Something.”

“Then this other cop; tall guy, he showed up, slides down the bank, lights up a cigarette. He was laughing, says, ‘Shit, Gunny, your car’s still on its wheels.’”

Monty turned to me. “Wendall. He stops laughing when he comes around, sees the rebar and the… blood. Not that much. Me and… Wendall, second later; we’re at the door. Your dad says, ‘Larry; could you tell Ruth…’ That’s all I got, ‘cause just then this Japanese lady, your mom, she shows up in…” Monty pointed to the Falcon before moving his finger toward the incline from the parking lot. “She slips as she comes off of the grade.”

“I ran over, helped her up.”

“You did, Digger; yes. Greg. Me and Wendall, Greg, too; we tried to keep her back, but she pushes between us, gets in the car on the passenger side. She seemed pretty… calm. Wendall wasn’t. Your dad says, ‘it’s fine, Larry.’ Wendall grabs the shovel.” Monty grabbed the shovel from Greg, thrusting it downward, hard, several times, into the stump until it stuck.

Monty was gasping for breath. “By this time, there’s so many cars, people, up, up on the highway. More sirens. I look in the car. The siren was off, but the light… it had popped off the roof, wire and all. It was still spinning; the engine was still… running. The, uh, your dad, he looks over at me, like maybe he knows me. He don’t.” Monty was breathing in gulps. “He looks at your mom. He says, ‘I always believed I rescued you.’ She reaches over, turns off the, the key, twists around, puts her arm, the same arm… around… him. And your mom kisses him, and she’s got blood… on her.”

Monty caught his breath. Most of it. “Then he, Wendall; he pulls me away from the window, pushes me back. He has this look in his eyes; it’s like he’s shaking his head, but he’s not. It’s just his eyes saying, you know, that it was over.”

The stump, somewhere around fourteen inches in diameter, had been cleanly cut with a chain saw. The part that had been removed was only a few feet away, visible in the heavy-bladed grass in a patch of green that surrounded the concrete box.

I looked at the slide marks and the crushed plants, the track we had come down. I imagined my mother coming down the bank, slipping, having to be helped back up. I imagined her in my father’s patrol car, reaching over, turning the key. I extended my right arm, moved it up until my hand was pointing up and at the highway. I moved my arm to the left, to where my father’s car slipped, sideways, on the new gravel. My flat hand represented the car as it slid, still sideways, to the bottom of the grade, plowing into the ancient river bottom, hitting the pile of rebar, one piece jammed into the stump, penetrating the door and my father like a bullet. I looked into the sun hanging just above the parking lot. I cupped my right hand, moved it, and then the left, above my eyes.

The shadow, the darkness, lasted but a moment. Another blinding light, and the spinning red light, and a vision of my father’s face as I passed him took over. Everything else was gone.

…

I was in shadow when the vision faded. I was on my knees. Gregory was directly in front of me. Monty was gone. I looked up toward the highway. Lee Anne Ransom, still in the light, had her camera aimed at Gregory and me. She waved. Gregory waved back as the reporter got into the Karmann Ghia and pulled away.

Gregory offered his ungloved right hand. I took it with both of mine. “Blisters,” I said as I stood up. “They turn into… callouses.”

“Not soon enough.”

“Gregory. How long?”

“How long you out for? Hmmm. ‘Bout a minute, I’d guess.”

I tried to remember what I had seen, or what I had imagined. Nothing. I remembered nothing. Not at that time. “Was I… shaking. I mean…”

“No, man; it was… weird; you were… it was like you was really… still. Like… church.”

“Did I… say anything?”

Gregory shook his head. I looked at him long enough that the motion turned into a nod. “You said ‘sorry’ a couple a times. Pretty much it. Hey, you good to… drive? I live in Oceanside, but I could…”

I followed Gregory to the corner between the parking lot’s fill and the established fill along the highway. Half-way up, he asked, “Who is… is there a… Julie?” My left foot slipped on the gravel. I caught my balance and continued up to the highway.

THANKS FOR READING. “Swamis” is copyrighted material, All changes are also protected. All rights are reserved for the author, Erwin A. Dence, Jr. THANKS for respecting that.

GOOD LUCK in finding the spot, the time, the right wave. More non-Swamis stuff on Sunday.