A few years ago I wrote a series of stories and, yes, poems that I put together in a collection I titled, “Mistaken for Angels.” Yes, I got a copyright. Vanity. Ego. Just in case. As with everything I have written, my plan for a novel or interconnected stories lost some of the connective-ness, random ideas popping in to complicate matters.

The underlying premise was that the story is more important than the telling, the style and the proper adjectives and structure less memorable than the absolute desire each of us has to tell our story.

It’s not my story; it’s fiction; and my remembering this story caused me to search through multiple thumb drives. The current portion of ancient struggles caused me to remember that I had written it; not about a particular place or time, but of many places and many times.

Tragedy begets tragedy.

I was raised to be a pacifist; yet, turning the channel, turning away, I do nothing. Nothing except, perhaps, to try to calm if not control my own confusion, my own outrage, my own anger.

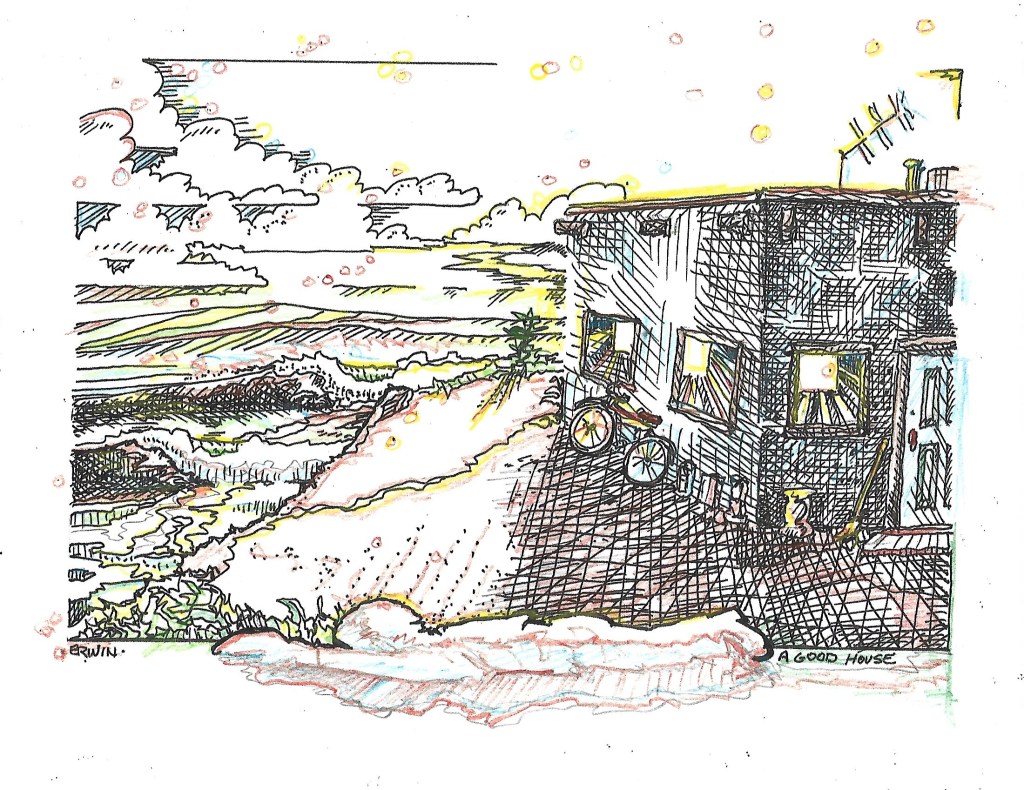

OH, since the location could be anywhere, on this (new) illustration (sketch if you must), I put in some waves in the background, making, possibly, A GOOD HOUSE that much better.

A Good House

We had a good house. This, you see, was the problem. It was, also, too close to the border. Some, those who think themselves brave, who think others will follow them, they call the disputed land on which the good house sits the ‘frontier.’ I call it ‘bloodlands.’ There has always been trouble. Wars go this way, then back; like waves on a lake.

My Father, he went to war- one of the wars- he pushed forward very bravely (so we were told), but came back very broken. The next wave took him for good.

Wave. Yes. Like a wave. We all knew he was already drowned. He was waiting for the next wave to wash his body away from… This is difficult to explain. “No faith left” he would say, staring toward the horizon.

My Mother, she had faith, and, with it, that certainty… I have heard it called fatalism. Ah, fancy term, that. It’s that knowledge that the darkness comes to each of us, to all of us. Fate and faith, they are, I think, related. “To have faith,” my Mother told us, my Sister and me, after our Brothers went, or were taken, made to fight, “you must have faith.”

This means, I think, that you must believe that having the faith sometimes works. Sometimes what we have the faith in, that things will be all right, can happen. I don’t know if I do believe this. My Mother did. Truly.

The snipers had done damage to the troops from our country. That is why they, our Soldiers, took to the houses. “Like a jar of water,” one of them told my Grandfather, who was weak and old, and had survived, he said, by never flying anyone’s flag, never taking a side. The Soldier held my Grandfather’s head against the rocks of the fireplace. He tapped it with a branch meant for the fire. He, the Soldier, explained this thing to my Mother, who, because she refused to cower as her Mother was, obviously was in charge.

He threw his hands apart to describe how a sniper’s bullet reacted with a soldier’s skull. “pheuuuuuuuh!” Then he laughed and let my Grandfather go.

“Okay,” he said, “your land; you don’t care what country it’s in. Fine.”

There was blood on this Soldier’s uniform. It (blood) dries almost black on the green. He smelled of gunpowder and body odor and death. They all carried sometimes multiple guns, and each had what you might call a machete. They called them something that would be more like ‘sword,’ and attributed a certain righteousness to its use. The Soldiers burned the blood from the blades in our fire, ate our food, complained about my Sister’s crying, and waited.

Soldiers, I now know, spend much time waiting. This is where their brains tell them many stories of why they should be afraid. They tell each other that they are not afraid, should not be afraid, they are and must be men. Yet, I could see these Soldiers had fear. Fear, someone else’s, looks like anger. I could feel my own fear. Like the Soldiers, I would hide it. I made my fear look like calmness. I could see everyone’s fear. Except my mother’s. She had the faith. I wanted to have the faith. I was ashamed to have, instead, the fear.

Fear is like a prayer, I think; or, maybe like a heavy, dark blanket, wrapped like a cloak, ready to be cast off, cast off quickly, when it is bravery that is needed.

Bravery, I’m afraid, is the ability to disregard what is known to be right. Bravery is a vicious thing. I no longer wish to be brave.

For some, it is better to be dead than brave.

Sorry. I must laugh a bit. The brave and cowardly are often thrown into the same grave.

“This is a very nice house,” another of the Soldiers said. He stood close to the window, lit a cigarette. “I think,” he said, “after the war, when we are free, I will take this house.” It was then the sniper’s bullet hit his neck. Both sides at once, it seemed. He was still smiling his dirty smile when his head snapped back. He rocked only a bit, and fell, crumpled, beside me where I sat. The cigarette was still in his mouth.

The first Soldier, and the others, ran outside, then away, leaving the dead one, blood splattered on our walls, making pools on our floor. We could hear guns going off, closer, then farther away. We thought, we hoped we were safe.

Briefly, we were.

These were the, it gets confusing; you might call them counter-insurgents. At dawn the insurgents came closer. Same smell, same uniforms (I thought at the time), different caps. They laughed when they saw how poor we were at trying to drag the body out. They kicked at it, shot it several more times, took things from it, threw it onto a truck with other bodies, some not in uniforms.

You can tell when the soul is gone, when a person becomes a body. Less. Almost nothing.

I don’t know where a soul goes. Somewhere better. I have seen those whose souls are gone, their bodies still…walking, eyes too wide open, too squinted down.

We would have been all right if the war had not slowed, the fighting ‘bogged-down’ in the hills; if the troops of our country had not fought so fiercely; if we had not had such a good house.

We had new guests not of our country. They thought themselves of a better country; bigger, older. This was not actually true, the bigger part, except for this short while. How small and pitiful our country must be, they said, to be so easily conquered.

I have no patience to explain why things went wrong. My Sister cried too much. It became night. Perhaps it was the darkness, the length of the nights. One of the soldiers said his grandfather might have worked on the masonry on our house, back when our country was still grand.

“If so,” my Grandfather said, “I would have paid him well. I always paid the workers well. They ate at our table.”

The mason’s Grandson looked at our table, smiled, but not nicely. Another Soldier, suddenly angry, perhaps because of how his Grandfather was treated, because of where his Grandfather took his meals, grabbed my Grandfather and pulled him outside. My Mother knew what this meant, and begged for her Father’s life. The Soldier slapped her for begging. Because she stood at the door and screamed “Butchers, murderers,” my grandmother was also pulled into the darkness. My Sister, holding onto our mother, kept crying. My Mother did not.

This is the fatalism of which I spoke, the belief that all will be tested.

And most fail.

I also did not cry. This is the faith, faith I had because my Mother had faith. The mason’s Grandson pulled my Sister away, shoved her toward me, told me, in my own language (they are really only slightly different) to keep her quiet. He moved his face close to my Mother’s, touched her breast. He said, Whores beg. Are you, then, a whore?” This was to humiliate her further.

I have learned this from war: To kill is not enough for some. To only, to merely kill is not enough to make the anger and the fear and the hatred cease.

“If I must be,” she said.

At this he laughed. “I am also the whore,” he said.

“My Children,” my Mother said to him. It was like a question. He, and the other Soldiers, now back from outside and leaning against our walls, shrugged and laughed together. The mason’s Grandson took his pistol belt off, holding the pistol in his left hand, moving it close to my Mother’s cheek.

“God will send a miracle,” she said to me. “Turn away,” she said.

I almost cried out at this moment. My Sister did. I put my hand over her mouth and prayed that I could have a man’s strength.

Prayers. Excuse me for laughing; just a little. Prayers are not answered as we expect.

It’s rare, I have learned, that a first mortar round can hit precisely. This one did, precisely where it was intended to land, and when I asked for it. The Soldier’s Grandfather had not been a roofer. No, not at all. Ha!

Like a jar of water, burst.

I kicked at his body when it was over, when the others ran, when more mortars rained down on the houses on the frontier.

Of prayer, I should add, speaking of the partial nature of the realization of prayer; my Mother did not survive this…this…I don’t know what they call this. It’s a tide, a tide, and we are the shore. I carved our Family’s name onto the mantel, underneath, to mark a claim when I return. I took the Soldier’s machete. After I’d chopped him with it; splattered his blood with it, I burned his blood from the blade in the fire.

By the time the Peacekeepers came, the roof was already patched, by my Grandfather and me. We also buried my Mother, dragged the soldiers’ bodies away from the house. My Grandparents would not leave. This was their home. That they were not soldiers was honored. That time. My Sister became one of the many refugees. Refuge means safety, of course. I prayed she would be safe. Yes. I told myself she was safe and fed and happy. That was my hope. Perhaps it is partially true. I became, as you know, a Soldier, a brave one, they say. I am still a Soldier; I wait, but I do not fear. I no longer even hate. I know what bravery is.

Oh, I see you don’t believe there could have been two miracles, two dead Soldiers in one house. Well, perhaps I lie. The results would be the same; the dried blood as black. Prayers answered.

When I was captured that first time, taken like a fool during one of the many truces, they called me John Doe number four hundred and thirty-four. I was, I now guess, eleven years old.