I know, I know; I’ve been working on the novel for soooooo long. I’ve put a lot of it on this site. Most or all of that has been changed. More like all of it except the baseline story; one which I have had a hard time (changed this from ‘fuck of a time’) reducing to a tagline.

There’s a procedure in selling books to major publishers, of course; daunting enough to dissuade even the most confident writers. AND, and, and we are all supposed to be capable of writing a story; and we all have stories. AND, believing that somewhere in all my millions of words written and changed, pages deleted, there’s a story, I have gotten to the point where I am leaping off some cliff and submitting “Swamis” to, today, seven agents.

Submission; even the word speaks of uncertainty, of decisions by others; SUBJECTIVE DECISIONS with the first round of decision-makers being the folks whose job it is to cut the volume of could-be-somethings down to those deemed worthy, or worthy-er.

Having something out there and out of our control is not that dissimilar to waiting for waves. Check the forecasts all we want, we can’t wish or hope waves into showing up. Yet, we try.

OH, AND if any of you are actual literary agents and believe you can sell “Swamis,” let me know. I’d certainly prefer a real surfer in my corner.

NOW, I did write an earlier query letter, and I did post it here. I also convinced several people to read it and give me feedback. So, thanks to KEITH DARROCK, DRUCILLA DENCE, ANDY and IZZY ROSANE. And then, of course, I rewrote the query. So, more thanks.

UPDATE ON MY SUPER FUN CAR- It was the in-line (as in, on a hose) heater control valve that broke on my thirty-year-old Volvo. Frustrated by my on line searching, I stopped by an auto parts store and tried to explain the whole thing. Kook-like. “It’s, like, kinda like a thermostat-looking thing, and it’s on this hose, and…” The already-flustered counter guy kept some appearance of patience, and found the part. “We’d have to order it.” Yeah. Then, knowing what I need, I went to YouTube to see if I can do the repair. Yes, pretty sure. Then, because it’s YouTube, on to brain surgery. No, probably not.

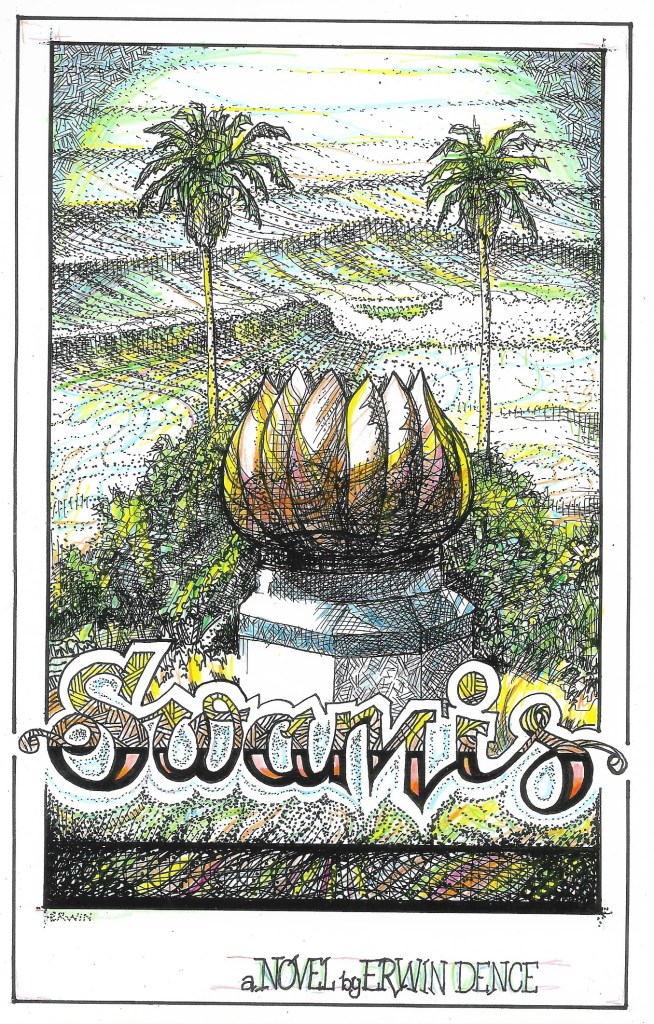

Query- “Swamis.” Fiction by Erwin A. Dence, Jr.

Marijuana, murder, surf, romance, and magic in a Southern California beach town in 1969.

Dear real surfers,

That my 92,000-word novel “Swamis” has become as much love story as murder mystery is a surprise to me. Almost. The action centers around the surf culture at Swamis Point in North San Diego County. It is 1969. An evolutionary/revolutionary period in surfing and beyond, to those who have only known crowds, this was a magical era.

Very close to turning 18, the narrator, Joseph Atsushi DeFreines, Jr., nicknamed Jody, has a history that includes a serious injury, time in a ‘special’ school, and violent outbursts. A top-level student and compulsive note taker, Joey is a socially awkward outsider who refuses to give oral reports. His two closest friends are other ‘inland cowboy’ surfers. Surf Friends. Joey wants to be accepted on the beach and in the lineup as a ‘local.’

Joey is desperately attracted to Julie Cole, one of a few girl surfers in the beach towns along Highway 101. Nicknamed Julia ‘Cold,’ just-turned-18-year-old Julie appears to be a spoiled, standoffish surfer chick, rabidly protected by her small group of friends. She is almost secretly brilliant and driven. Julie, like Joey, has personal trauma in her past.

Joey is the son of a Japanese ‘war bride’ and an ex-Marine. County Sheriff’s Office detective Joseph DeFreines, who says, “The world works on an acceptable level of corruption” is trying and failing to maintain that level. Marijuana is becoming a leading cash crop in his rural and small town jurisdiction. The completion of I-5 is supercharging population growth.

Julie’s father, David Cole, is a certified public accountant who may, with help from outwardly upright citizens, be laundering increasing amounts of drug money. Julie’s mother, Judith, moves from fixer-upper to fixer-upper in a housing market about to explode. She may also be the head of a group growing, packaging, transporting, and selling marijuana. Once grown in orchards and sold to friends of friends, the product is moved through Orange County middlemen to a larger, more profitable, and more dangerous market, Los Angeles.

Joey and Julie, concentrating on studying and surfing, had been rather blissfully unaware of what was going on around them. Joey’s father’s death, for which Joey may be responsible, has connections to the murder of Chulo, a beach evangelist and drug dealer set alight next to the white, pristine, gold lotus-adorned walls of a religious compound that gives Swamis its name.

Finding Chulo’s murderer, with those on all sides believing Joey has inside information, pushes Joey and Julie together.

There is an interconnectedness between all the supporting characters, each with a story, each as real as I can render them.

“Swamis” was never intended to be an easy beach read. And it isn’t.

I am of this period and place, with brothers and friends who were very involved in the marijuana/drug culture, both sides. I was not. It is very convenient that a Swami, like a detective, like many of the characters in the novel, is a ‘seeker of truth.’

I have written articles, poems, short stories, screenplays, and two other novels, some moving to the ‘almost’ sold category. I had a column “So, Anyway…” in the “Port Townsend Leader” for ten years, I’ve written, illustrated, and self-published several books of local northwest interest. I started a surf-centric website (blog) in 2013: realsurfers.net.

After many, many edits and complete rewrites, I believe the manuscript is ready for the next step. Thank you for your time and consideration, Erwin A. Dence, Jr. (360) 774-6354

Illustrations for “SWAMIS” by the author, Erwin A. Dence, Jr.

“SWAMIS” A novel by Erwin A. Dence, Jr.

The surf, the murder and the mystery, all the other stories; “Swamis” was always going to be about Julie. And me. Julie and me. And… Magic.

CHAPTER ONE- MONDAY, NOVEMBER 13, 1969

“Notes. I take a lot of… notes, but… your stack is bigger. Is that my permanent record?”

“Not sure why you take notes. You seem to remember, like, everything. Records. Records are for… later, for someone else.”

“As are notes. And maybe, some time I… won’t remember.”

“You brought them in; so, can I assume that your mother…”

“Yeah. Snoopy. Detective’s wife. We took the Falcon. I drove, my mother…”

“Snooped. Sure. Would you read me something from one of your notebooks? Your choice. Maybe something about… surfing.”

“Kind of boring, but… give me a second. Okay. ‘The allure of waves was too much, I’m told, for an almost three-year-old, running, naked, into them. I remember how the light shone through the shorebreak waves; the streaks of foam sucked into them. I remember the shock of cold water and the force with which the third wave knocked me down, the pressure that held me down, my struggle for air, my mother clutching me out and into the glare by one arm.’”

“Impressive. When did you write this? You had most of it memorized.”

“Some. But, if I wrote it recently, Doctor Peters. This all happening before the… accident; that would be me… creating a story from fragments. Wouldn’t it?”

“Memories. Dreams. We can’t know how much of life is created from… fragments. But, please, Joey; the basketball practice story; I didn’t get a chance to write it down. So, the guy…”

“I’m not here because of that… offense.”

“I am aware. Just… humor me.”

“Basketball. Freshman team. Locker room. They staggered practice. I was… slow… getting dressed. Bus schedules. He… FFA guy… Future Farmers. JV. Tall, skinny, naked, foot up on a bench; he said I had a pretty big… dick… for a Jap. I said, ‘Thank you.’ just as the Varsity players came in. Most stood behind him. He said, ‘Oh, that’s right; your daddy; he’s all dick.’ Big laugh.”

“’Detective,’ I said. ‘And, Rusty, I am sorry about your brother at the water fountain. I’m on probation already… and I’m off the wrestling team, and…’ I talk really fast when I’m… forced to… talk. I’m sure you’ve made note. I said, ‘I don’t want to cut my hand… on your big buck teeth.’ Bigger laugh. Varsity guys were going, ‘Whoa!’ Rusty was… embarrassed. His brother… That incident’s in the records. Fourth grade. Three broken teeth. Year after I… came back. That’s why the buck teeth thing… Not funny. Joke.”

“Joey. You’re picturing it… the incident. You are.”

“No. I… Yes. I quite vividly picture, or imagine, perhaps… incidents. In both of those cases, I tried to do what my father taught me; tried and failed. ‘Walking away is not backing down,’ he said. Anyway. Basketball. I never had a shot. Good passer, great hip check.”

“Rusty… He charged at you?”

“He closed his eyes. I didn’t. Another thing I got from my father. ‘Eyes open, Jody!’”

“All right. So, so, so… Let’s talk about the incident for which you are here. You had a foot on… a student’s throat. Yes? Yes. He was, as you confirm, already on the ground… faking having a seizure. He wasn’t a threat to you; wasn’t charging at you. Have you considered…?”

“The bullied becomes the bully? It’s… easy, simple, logical… not new; and I have… considered it. Let’s just say it’s true. I am… this is my story… trying to mend my ways. Look, Grant’s dad alleges… assault. I’m… I get it; I’m almost eighteen. Grant claims he and his buddies were just… fooling around; adolescent… fun; I can, conceivably… claim, and I have, the same.”

“But it wasn’t… fun… for you?”

“It… kind of… was. Time’s up. My mom’s… waiting.”

“Joey… I am, can be… the bully here. So… sit the fuck back down!”

CHAPTER TWO- SATURDAY, AUGUST 14, 1965

My mother took my younger brother, Freddy, and me to the beach at what became the San Elijo campground. Almost or just opened, it runs along the bluff from Pipes to Cardiff Reef. We were at the third stairway from the north end. I was attempting to surf; Freddy was playing in the sand. My mother was collecting driftwood for a fire. The waves were small. Pushing my way out, walking, jumping over the lines, I was turning and throwing my board into the soup, standing up, awkwardly, and riding straight in; butt out, hands out, stupidest grin on my face. “Surfin’!”

A girl, about my age, was riding waves. Not awkwardly. Smoothly. Not straight, but across. She wouldn’t have wiped out on the third ride I witnessed if I hadn’t been in her way, almost frozen, surprised by a wave face so thin and clean I still swear I could see through it.

I let my board go, upside down, broach to the waves, and chased down hers. When I pushed it back toward her, she said, “It’s you.”

“Me?” I had to look at her and reimagine the moments immediately before she spoke. She was wading toward me. She pushed the hair away from both sides of her face. She looked toward the beach. She looked back. Her eyes were green and seemed, somehow, as transparent as I had imagined the waves to be. “It’s you.”

“No. No, I’m… not… Who are you?”

“Someone who stays away from cops… And their kids.” She wasn’t going to thank me for grabbing her board. “Surfing isn’t easy, you know. All the real surfer guys are assholes.” She turned, threw herself onto her board, and started paddling. “I’d give it up If I were you.”

“Assholes,” I said as I retrieved my board. “I’m a well-known asshole.” I walked and pushed and paddled and made my way out to where the girl was sitting. She looked out to sea. She looked toward the shore. It was a lull, too long for her not to turn toward me as I attempted to knee paddle.

“We can’t be friends, Junior,” she said.

“No? What about when I… get to the point where I surf way better than you? Still, no?”

The girl turned away again. Not as long this time. “You coming back tomorrow?”

“No. Sunday. Church. My mom… We… Church.”

“Church,” she said. “My mom and I… Well, me; I… surf.”

The girl paddled over and pushed me off my board. The first wave of a set took it in. She turned and caught the next wave. I watched her from behind it. Graceful. “Julia Cole,” I said, loud enough for her to hear. “Your friends call you Julie.” I said that to myself.

CHAPTER THREE- SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 15, 1968

My nine-six Surfboards Hawaii pintail was on the Falcon’s rust and chrome factory racks. I was headed along Neptune, from Grandview to Moonlight Beach. The bluff side of Neptune was either garage or gate and fence, or hedge, tight to the road. There were few views of the water. I was, no doubt, smiling, remembering something from that morning’s session.

There had been six surfers, including me, at the outside lineup, the preferred takeoff spot. They all knew each other. If one of them hadn’t known about the asshole detective’s son, others had clued him in. There was no way the local crew and acceptable friends would allow me to catch a set wave. No; maybe a wave all of them missed or none of them wanted. Or one would act as if he was going to take off any wave I wanted, just to keep me off it.

As the first one in the water, before dawn, I had surfed the peak, selecting the wave I thought might be the best of a set. Two other surfers came out. Okay. Three more surfers came out. One of them, Sid, paddled past me, making him the farthest one out in a triangular cluster that matched the peak of waves approaching. I knew who Sid was. By reputation. A set wave came in. I had been waiting. It was my wave. I paddled past Sid, paddled and took off. Sid dropped in on me. I said something like, “Hey!”

Rather than speed down the line or pull out, Sid stalled. It was either hit him or bail. I bailed. Sid said, “Hey!” Louder. He looked at me, cranked a turn at the last moment. He made the wave. I swam.

“I didn’t do anything wrong,” I said, approaching the lineup. The four other surfers held their laughter until Sid maneuvered his board around, laughed and said, “Wrong, Junior; you broke the locals rule.” Sid pointed to the lefts, the waves perceived as not being as good, on the other side of a real or imagined channel. “Local’s rule. Get it?” Trying to ignore the taunts of the others, I caught an insider and moved over.

After three lefts, surfed, I believed, with a certain urgency and a definite aggression, I prone-paddled back to the rights, tacking back and forth. A wave was approaching, a decently sized set wave. I wanted it.

“Outside!” I yelled, loud enough that five surfers, including Sid, started paddling for the horizon. I paddled at an angle, lined up the wave at the peak. Though the takeoff was late, I made the drop, rode the wave into the closeout section, pulling off the highest roller coaster I had ever even attempted. I dropped to my board and proned in. I kept my back to the water as I exited, not daring to look back or to look up at the surfers on the bluff, hooting and pointing.

I did look up for a moment as I grabbed my towel where it was stashed, visible from the water, on the low part of the bluff, my keys and wallet and cigarettes rolled up in it. Tromping up the washout to Neptune Avenue, I tried not to smile.

Driving my 1964 Falcon station wagon, almost to Moonlight Beach, a late fifties model Volkswagen camper van, two-tone, white over gray, was blocking the southbound lane. Black smoke was coming out of the open engine compartment. Three teenagers, locals, my age, were standing behind the bus: Two young men, Duncan Burgess and Rincon Ronny, on the right side, one young woman, Monica, on the left. Locals.

There was more room on the northbound side. I pulled over, squeezed out between the door and someone’s bougainvillea hedge, and walked into the middle of the street, fifteen feet behind the van. “Can I help?”

Duncan, Ronny, and Monica were dressed as if they had surfed but were going to check somewhere else: Nylon windbreakers, towels around their waists. Duncan’s and Monica’s jackets were red with white, horizontal stripes that differed in number and thickness. Ronny was wearing a dark blue windbreaker with a white, vertical strip, a “Yater” patch sewn on. Each of the three looked at me, and looked back at each other, then at the smoking engine. The movement of their heads said, “No.”

Someone stepped out of an opening in the hedge on the bluff side of the road, pretty much even with me. I was startled. I took three sideways steps before I regained my balance.

Julia Cole. Perfectly balanced. She was wearing an oversized V-neck sweater that almost covered boys’ nylon trunks. Her legs were bare, tan, her feet undersized for the huarache sandals she was wearing. She looked upset, but more angry than sad. But then… she almost laughed. I managed a smile.

“It’s you,” she said. It was. Me. “Are you a mechanic?” I shook my head, took another step toward the middle of the road, away from her. “An Angel?” Another head shake, another step. She took two more steps toward me. We were close. She seemed to be studying me, moving her head and eyes as if she might learn more from an only slightly different angle.

I couldn’t continue to study Julia Cole. I looked past her. Her friends looked at her, then looked at each other, then looked, again, at the subsiding smoke and the growing pool of oil on the pavement. “We saw what you did,” she said. I turned toward her. “From the bluff.” Her voice was a whisper when she added, “Outside,” the fingers of her right hand out, but twisting, pulling into her palm, little finger first, as her hand itself twisted. “Outside,” she said again, slightly louder.

“Oh. Yes. It… worked.”

“Once. Maybe Sid… appreciated it.” She shook her head. “No.”

I shook my head. “Once.” I couldn’t help focusing on Julia Cole’s eyes. “I had to do it.”

“Of course.” By the time I shifted my focus from Julia Cole’s face to her right hand, it had become a fist, soft rather than tight. “Challenge the… hierarchy.”

I had no response. Julia Cole moved her arm slowly across her body, stopping for a moment just under the parts of her sweater dampened by her bathing suit top. Breasts. I looked back into her eyes for the next moment. Green. Translucent. She moved her right hand, just away from her body and up. She cupped her chin, thumb on one cheek, fingers lifting, pointer finger first, drumming, pinkie finger first. Three times. She pulled her hand away from her face, reaching toward me. Her hand stopped. She was about to say something.

“Julie!” It was Duncan. Julie, Julia Cole didn’t look around. She lowered her hand and took another step closer to me. In a ridiculous overreaction, I jerked away from her.

“I was going to say, Junior…” Julia was smiling. I may have grinned. Another uncontrolled reaction. “I could… probably use… If you were an… attorney.”

“I’m not… Not… yet.”

Julia Cole loosened the tie holding her hair. Sun-bleached at the ends, dirty blonde at the roots. She used the fingers of both hands to straighten it.

“I can… give you a ride… Julie, I mean… Julia… Cole.”

“Look, Fallbrook…” It was Duncan. Again. He walked toward us, Julia Cole and me. “We’re fine.” He extended a hand toward Julia. She did a half-turn, sidestep. Fluid. Duncan kept looking at me. Not in a friendly way. He put his right hand on Julia Cole’s left shoulder.

Julia Cole allowed it. She was still smiling, still studying me. “Phone booth?” I asked.. “There’s one at… I’m heading for Swamis.”

A car come up behind me. I wasn’t aware. Rincon Ronny and Monica watched it. Duncan backed toward the shoulder. Julia and I looked at each other for another moment. “You really should get out of the street… Junior.”

“Joey,” I said. “Joey.”

She could have said, “Julie.” Or “Julia.” She said neither. She could have said, “Joey.”

No one got a ride. I checked out Beacons and Stone Steps and Swamis. The VW bus was gone when I drove back by. Dirt from under someone’s hedge was scattered over the oil, some of it seeping through.

CHAPTER FOUR- WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 23, 1968

Christmas vacation. I had surfed, but I wanted a few more rides. Or many more. I had the time, and I had the second-best parking spot in the full lot at Swamis- front row, two cars off center. It was cool but sunny. I was standing, dead center, in front of the Falcon, leaning over the hood. I checked my diver’s watch. It was fogged up. I shook my wrist, removed the watch, set it on the part of the Falcon’s hood my spread-out beach towel didn’t cover; directly over the radiator, the face of the watch facing the ocean and the sun.

Spread out on the towel was a quart of chocolate milk in a waxed cardboard container, the spout open; a lunch sack, light blue, open; an apple; a partial pack of Marlboros, hard pack, open, a book of paper matches inside; three Pee-Chee folders. One of the folders was open. A red notebook, writing on both sides of most pages, was open, five or six pages from the back.

A car stopped immediately behind the Falcon. Three doors slammed. Three teenagers, a year or so younger than me, ran down the left side of my car and to the bluff. Jumping and gesturing, each shouted assessments of the conditions. “Epic!” and “So… bitchin’!”

They looked at each other. They looked over me and at their car, idling in the lane. They looked at me. The tallest of the three, with a bad complexion, his hair parted in the middle, shirtless, with three strands of love beads around his neck, took a step toward me. “Hey, man.” He lifted two of the strands. “Going out or been out?”

“Both. Man.”

“Both?” Love Beads guy moved closer, patting the beads. “Both. Uh huh.”

“Good spot,” the driver, with bottle bleached hair, a striped Beach Boys shirt, and khaki pants, said. I nodded. Politely. I smiled, politely, and looked back and down at my notebooks. He asked, “You a local?”

I shifted the notebooks, took out the one on the bottom, light blue, opened it, turned, half sat on my car, and looked out at the lineup, half hoping my non-answer was enough for the obvious non-locals.

A car honked behind us. Love Beads raised his voice enough to say, “At least go get the boards, Shorty.” The Driver ran toward his car. As Shorty reluctantly walked away from the bluff, Love Beads gave him a shove, pushing him into me.

Shorty threw both hands out to signal it wasn’t his fault. Behind him, Love Beads Guy said, “You fuckers down here are fuckin’ greedy.”

“Fuck you, Brian,” Shorty said before running out and into the lane.

Love Beads Guy, Brian, moved directly in front of me. He puffed out his chest a bit. He looked a bit fierce. Or he attempted to. “You sure you’re not leaving?”

I twisted my left arm behind my back and set the notebook down and picked up my watch. When I brought my arm back around, very quickly, Brian twitched. I smiled. I held my watch by the band, close to its face. I shook it. Hard. Three quick strokes, then tapped it, three times, with the pointer finger of my right hand. “The joke, you see, Brian, is that, once it gets filled up with water, no more can get in. Hence, Waterproof.” I put the watch on. “Nope, don’t have to leave yet… Brian.”

Brian was glowering, tensed-up. “Brian,” Shorty said as he carried two boards over to the bluff and set them down, “You could, you know, help.”

Brian raised his right hand, threw it out to his left and swung it back. I took the gesture to mean ‘shut up and keep walking.’ I chuckled. Brian moved his right hand closer to my face, pointer finger up.

I moved my face closer to his hand, then leaned back, feigning an inability to focus. “Brian,” I said, “I have a history…” Brian smirked. “I used to… strike out, and quite violently… when I felt threatened.” I blinked. “Brian.”

Brian looked around as if Shorty, packing the third board past us, might back him up. “Quite violently?”

“Used to… Brian. Suddenly and… violently.” I nodded and rolled my eyes. I moved closer to his face. “But now… My father taught me there are times to react and times to… take a moment, assess the situation, but… watch, and be ready. It’s like… gunfights, in the movies. If someone… is ready to… strike, I strike first. I mean, I can. Because… I’m ready.” I moved my face back from Brian’s and smiled. “Everyone… people are hoping the surfing is… helping. I am not… sure. I’m on… probation, currently; I get to go to La Jolla every Monday, talk to a… shrink. Court ordered. So…” I took a deep breath, gave Brian a peace sign.

“Brian,” Beach Boy, at the driver’s door of his parent’s car said, “we’ll get a spot.”

“Wind’s coming up, Brian,” I said, pointing to the boards. “Better get on it.”

“Oh, I have your permission. No! Fuck you, Jap!” Brian moved back and into some version of a fighting stance as he said it.

“Brian. I’m, uh, assessing.” I folded my hands across my chest.

Brian may have said more. He moved even closer, his mouth moving, his face out of focus; background, overlapped by, superimposed with, a succession of bullies with faces too close to mine; kids from school, third grade to high school. I couldn’t hear them, either. Taunts. I knew the words: “Retard!” “Idiot!” “What’s wrong with you?”

My father’s voice cut through the others. “They don’t know you, Jody. It’s all a joke. Laugh.” In this vision, or spell, or episode, each of my alleged tormentors, all of them boys, fell away. Each face was bracketed by and punctuated with a blink of a red light. Every three seconds. Approximately.

One face belonged to a nine-year-old boy, a look of shock that would become pain on his face. He was falling back and down, blood coming out of his mouth. Red light. I looked at the school drinking fountain. A bit of blood. Red light. I saw more faces. The red lights became weaker, and with them, the images.

The lighting changed. More silver than blue. Cold light. I saw my father’s face, and mine, in the bathroom mirror. Faces; his short, almost blond hair, almost curly, eyes impossibly blue; my hair straight and black, my eyes almost black. “Jody, just… smile.” I did. Big smile. “No, son; not that smile.”

I smiled. That smile.

Brian’s face came back into focus. I looked past him, out to the kelp beds and beyond. “Wind’s picking up.” I paused. “Wait. Did I already say that… Brian?”

I turned toward the Falcon, closed the blue notebook, set it on one side of the open Pee-Chee, picked up the red notebook from the other side. There were crude sketches of dark waves and cartoonish surfers on the cover. I opened it and started writing.

“Wind is picking up.” I may have spun around a bit quickly, hands in a pre-fight position. It was Rincon Ronny in a shortjohn wetsuit, a board under his arm. Ronny nodded toward the stairs. “Fun guys.” He leaned away and laughed. I relaxed my hands and my stance. “The one dude, with the Hippie beads. Shirtless.”

“Brian. Shirtless.”

“Don’t want to know his name.” There was a delay. “Fuck, man; he was scared shitless.”

“It’ll wear off.” I held the notebook up, showed Ronny the page with ‘Brian and friends’ written in larger-than-necessary block letters, scratched out ‘Brian,’ and closed the notebook. “By the time they get back to wherever they’re from, unnamed dude would’ve kicked my ass.” I looked around to see if any of Ronny’s friends were with him. “I was… polite, Rincon Ronny.”

“Polite. Yeah. From what I saw. Yeah. And… it’s just… Ronny. Now.”

I had to think about what Ronny might have seen, how long I was in whatever state I was in. Out. I started gathering my belongings, pulling up the edges of my towel. “I just didn’t want to give my spot to… fuckers. Where are you… parked?”

“I… walked.”

I had to smile and nod. “You… walked.”

Ronny nodded and looked at my shortjohn wetsuit, laid out over my board. “Custom. Impressive.” I nodded and smiled. “One thing, Junior; those… fuckers, they won’t fuck with you in the water.”

“Joey,” I said. “I mean, not that you want to know, and… Ronny, someone will.”

Ronny mouthed, “Joey,” and did a combination blink/nod. “Yeah. It’s… Swamis. Joey.”

Ronny looked at the waves, back at me. A gust of west wind blew the cover of my green notebook open. “Julie” was written in almost unreadably psychedelic letters across pages eight and nine. “Julie.” Hopefully unreadable.

I repeated Ronny’s words mentally, careful not to mouth them. “From what I saw. Joey.”

CHAPTER FIVE- THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 27, 1969

Our house in the hills between Fallbrook and Bonsall was a split level, stucco house, aluminum sash windows, composite roof. Someone else had started building from some plans purchased from a catalog. My parents could save money, they were told, by finishing the lower level and the garage. They could replace the plywood shed at the edge of a corral with a small barn that would provide room for a horse, a side area for hay and tack. New fencing. More trees. A garden. A covered patio off the kitchen, or, perhaps, a bay window.

Almost none of this ever happened. My father promised the patio, and then the bay window. He was working on it, but he was working. Working. There was, outside the sliding door, a concrete slab, with paving stones leading around the corner and down to the driveway. The two-story portion of the house featured a plate glass window, four foot high and eight feet wide, in total, with crank out, aluminum sash windows on either side. This window offered a view to the west, over scrubby trees and deep arroyos, of the hills, some rounded, others more jagged, with ancient boulders visible on all of them. Mission Avenue was hidden below and between. Mission, the road that linked Fallbrook with Bonsall, Vista, Oceanside, everywhere west, everywhere worth going to.

Looking out this window, I felt almost level with those hills. Morning light, descending, brought out the details of the ribs and rocks. Afternoon shadows crept from it until the hills once again became a blank shape. There were waves of hills in irregular lines between my hills and the unseen ocean. I had spent time looking away from my studies, imagining the hills in timelapse, the sun setting at one place in winter, another in summer, lines off clouds held back at the ridgeline, breaking over the top; torn, scattering. I had imagined the block as transparent, the ocean visible, late afternoon sunlight reflected off the water and into the empty skies.

…

The light outside was still neutral when I moved to the dinette table in the kitchen, a bowl of oatmeal, a tab of butter on top of it, in front of me. There was a glass pitcher of milk between my setting and the other two. There were four lunch sacks on the counter. Two were a light blue, one was a shade more orange than pink, the fourth was the standard lunch sack brown. My mother, already dressed and ready for work, took a carton of Lucky Strikes from a cupboard and put a pack into the brown lunch sack.

She looked out the window over the sink. She sniffled.

My father, in one of his everyday detective suits; coat unbuttoned, tie untied; leaned over from the head of the table. “Go get it, Jody.” The ‘now’ part of the command was unspoken. His voice was calm. Almost always. I didn’t move. I didn’t look up from my oatmeal. “Stanford, Jody; you didn’t think they’d send a copy to the school?”

My father’s questions demanded an answer or a response. Crying or lying were not acceptable options. “I did… consider the possibility.”

“Of course. Now, Jody, consider everything you have to do to be ready. Got it?”

Making eye contact was critical in these situations. Required, if for no other reason than to show I was sorry, remorseful. I wasn’t crying.

All original illustrations and writing on realsurfers.net is protected by copyright. All rights reserved by Erwin A. Dence, Jr. THANKS FOR CHECKING! FIND SOME SURF!

You work hard, Erwin!!!

drew

>