…and, perhaps, something, not too deep or crazy, on the chains of morality.

BUT FIRST- I asked for a followup report from TOM BURNS, judge at last weekend’s WESTPORT LONGBOARD CLASSIC. “What I can tell you, Erwin, is that the best surfers won.” OKAY, so, guessing, normal contest deal, competitors butt hurt for underscoring, local bias, etc.

BUT TODAY, the CAPE KIWANDA LONGBOARD CLASSIC, in its 25th year, is Live streaming (got it on my big screen- doesn’t make the waves look better- WAIT!- just saw a rare good one). I did scroll through some yesterday, saw a local surfer from the Olympic Peninsula not advance. No doubt underscored.

EQUINOX STUFF- I tuned into local Port Townsend radio station KPTZ yesterday, expecting to hear something about organic gardening or cold water plunging. Instead, I heard “Summer’s Almost Gone” by the DOORS. What! It was enough to keep me from checking out the news on NPR. Yeah! THE MEMORIES the song brought to me were enough to push me to call my old friend, RAY HICKS. And I would have if September isn’t the craziest time of the year for house painters.

1968. RAY, BILL BUEL, PHILLIP HARPER, and I were headed back to Fallbrook from a surf session at Oceanside or Grandview, smoking cigarettes, listening to our favorite band on a 4 track tape. The song comes on. We’re probably singing along. There’s a fill after each of the verses. “Where will we be… when the summer’s gone?” My adding “We’ll be in school” seemed to fit perfectly, heading toward our Senior year. My cohorts disagreed. Vigorously.

RAY HICKS, 1968

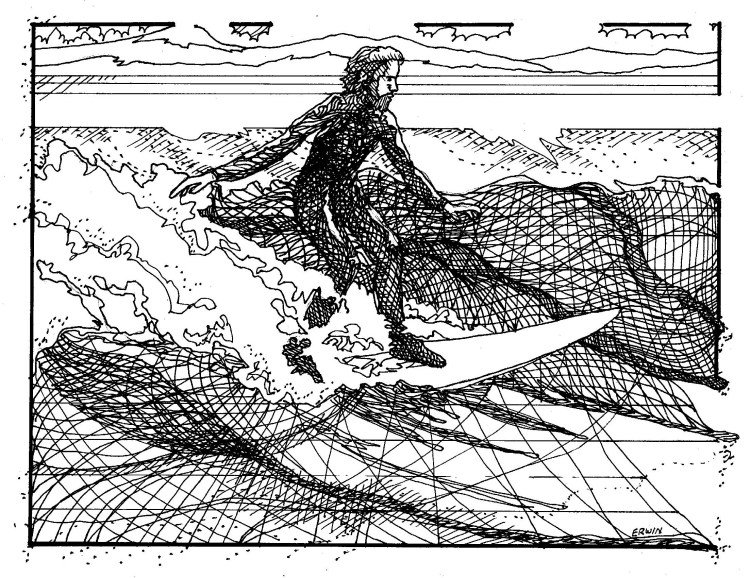

This is not the STRAIT OF JUAN DE FUCA, but it is a similar view. I have always kept track of where the sun sets as each year spins on. The foothills of Camp Pendleton have long been replaced by the eastern slopes of the Olympic Mountains, the sun moving from south to north to south across the ridges. I don’t keep track of the mysterious tracks of the moon; full moon, yes; connected to the tides changes, critical element of surf forecasting/guessing. So, we’re halfway to winter, surfers switching the forecast logic with the hope of swell, the ebbing and flowing hope and, yes, anticipation. Winter’s almost here. Almost here. Where will we be, when the winter’s here… I guess we’ll see.

THE MORALITY THING- We are all taught some guidelines to what constitutes a moral life. Restraints, perhaps. No, definitely. We all want to justify our actions, twisting the boundaries when necessary. No, I’m not making excuses for wave-hogging. It’s sociopathic, possibly, occasionally, doing something one knows is wrong, and then doing it again. STILL, we generally behave within our individually-set boundaries. Almost as if we have to. THE POLITICAL PART- If you are taught from birth to take advantage whenever you can, to screw over others in every interaction, pay attorneys rather than those providing services or products and then ask for my vote, well… no.

CHAPTER SIX- TUESDAY, MARCH 4, 1969

It was still early afternoon. I was in the living room, ignoring everything behind me, facing but not really seeing anything out the west-facing window. A Santa Ana condition had broken down, and a thousand-foot-high wall of fog had pushed its way up the valleys. The house was situated high enough that the cloud would occasionally clear away, the sun brighter than ever. The heat and humidity, raised by the number of people in our house, caused a fog of condensation on the plate glass.

Below me, cars were parked in a mostly random way in the area between the house and the separate and unfinished garage, and the corral. Continued use had created a de facto circular driveway up the slight rise from the worn and pitted gravel driveway, across the struggling lawn, and up to the concrete pad at the foot of the wooden steps and front porch.

A bright yellow 1964 Cadillac Coupe De Ville convertible, black top up, was parked closest to the door. Other vehicles were arranged on the clumpy grass that filled in areas of ignored earth. Later arrivals parked on the lower area. The Falcon was parked close to the county road in keeping with my parking obsession; with getting in, getting out, getting away.

I was vaguely aware of the music coming from the turntable built into the Danish modern console in the living room. Stereo. Big speakers in opposite corners of the room, the volume where my father had set it, too low to compete with the conversations among the increasing crowd, the little groups spread around the room. Some were louder than others. Praise and sympathy, laughs cut short out of respect. Decorum.

Someone had put on a record of piano music; Liberace, or someone. My father’s choice would have been from the cowboy side of country/western; high octave voices capable of yodeling, lonesome trails and tumbling tumbleweeds, the occasional polka. My mother preferred show tunes with duets and ballads by men with deep, resonant voices, voices like her husband’s, Joseph Jeremiah DeFreines.

These would not have been my father’s choice of mourners. “Funerals,” he would say, “Are better than weddings.” He would pause, appropriately, before adding, “You don’t need an invite or a gift.”

Someone behind me repeated that line, mistiming the pause, his voice scratchy and high. I turned around. It was Mister Dewey. A high school social studies teacher, he sold insurance policies out of his rented house on Alvarado. His right hand was out. I didn’t believe shaking hands was expected of me on this day.

“You know my daughter, Penelope,” he said, dropping his hand.

“Penny,” I said. “Yes, since… third grade.” Penny, in a black dress, was beside Mr. Dewey, her awkwardness so much more obvious than that of the other mourners. I did shake her hand. “Penny, thanks for coming.” I did try to smile, politely. Penny tried not to. Braces.

I looked at Mr. Dewey too closely, for too long, trying to determine if he and I were remembering the same incident I was. His expression said he was.

When I refocused, Mister Dewey and the two people he had been talking with previously, a man and Mrs. Dewey, were several feet over from where they had been. I half-smiled at the woman. She half-smiled and turned away. She wasn’t the first to react this way. If I didn’t know how to look at the mourners, many of them did not know how to look at me, troubled son of the deceased detective.

If I was troubled, I wasn’t trying too hard to hide it. I was trying to maintain control. “Don’t spaz out,” I whispered, to myself. It wasn’t a time to retreat into memory, not at the memorial for my father. The wake.

Too late.

“Bleeding heart liberal, that Mister Dewey,” my father was telling my mother, ten-thirty on a school night, me still studying at the dinette table. “He figures we should teach sex education. I told him that we don’t teach swimming in school, and that, for most people, sex… comes… naturally. That didn’t get much of a laugh at the school board meeting.”

“Teenage pregnancies, Joe.”

“Yes, Ruth.” My father touched his wife on the cheek. “Those… happen.”

“Freddy and I both took swimming lessons at Potter Junior High, Dad. Not part of the curriculum, but…”

“Save it for college debate class, Jody. We grownups… aren’t talking about swimming.”

Taking a deep breath, my hope was that the mourners might think it was grief rather than some affliction. Out the big window, a San Diego Sheriff’s Office patrol car was parked near where our driveway hit the county road. The uniformed Deputy, still called “New Guy,” assigned to stand there, motioned a car in. He looked around, went to the downhill side of his patrol car. He opened both side doors and, it had to be, took a leak between them. Practical.

The next vehicle, thirty seconds later, was a delivery van painted a brighter yellow than the Hayes’ Cadillac. Deputy New Guy waved it through. I noticed two fat, early sixties popout surfboards on the roof, nine-foot-six or longer, skegs in the outdated ‘d’ style. One was an ugly green, fading, the other, once a bright red, was almost pink. Decorations, obviously, they appeared to be permanently attached to a bolted-on rack. The van was halfway to the house before I got a chance to read the side. “Flowers by Hayes brighten your days.” Leucadia phone number.

Hayes, as in Gustavo and Consuela Hayes. As in Jumper Hayes.

A man got out of the van’s driver’s seat, almost directly below me. Chulo. I knew him from the beach. Surfer. Jumper’s partner in ‘the great avocado robbery’ that sent them both away, Chulo returning, reborn, evangelizing on the beach, with a permanent limp.

Chulo’s long black hair was pulled back and tied; his beard tied with a piece of leather. He was wearing black jeans, sandals, and a day-glow, almost chartreuse t-shirt with “Flowers by Hayes” in white. Chulo looked up at the window, just for a moment, before reaching back into the front seat, pulling out an artist’s style smock in a softer yellow. He pulled it over his head, looked up for another moment before limping toward the back of the van.

The immediate image I pulled from my mental file was of Chulo on the beach, dressed in his Jesus Saves attire: The dirty robe, rope belt, oversized wooden cross around his neck. Same sandals. No socks.

Looking into the glare, I closed my eyes. Though I was in the window with forty-six people behind me, I was gone. Elsewhere.

…

I was tapping on the steering wheel of my mother’s gray Volvo, two cars behind my Falcon, four cars behind a converted school bus with “Follow me” painted in rough letters on the diesel smoke stained back. The Jesus Saves bus was heading into a setting sun, white smoke coming out of the tailpipes. Our caravan was just east of the Bonsall Bridge, the bus to the right of the lane, moving slowly.

My mother, in the Falcon, followed another car around the bus. Another car followed her, all of them disappearing into the glare. I gunned it.

I was in the glare. There was a red light, pulsating, coming straight at me. There was a sound, a siren, blaring. I was floating. My father’s face was to my left, looking at me. Jesus was to my right, pointing forward.

This wasn’t real. I had to pull out of this. I couldn’t.

The Jesus Saves bus stopped on the side of the road, front tires in the ditch. The Volvo was stopped at a crazy angle in front of the bus. I was frantic, confused. I heard honking. Chulo, ion the Jesus Saves bus. He gave me a signal to go. Go. I backed the Volvo up, spun a turn toward the highway. I looked for my father’s car. I didn’t see it. The traffic was stopped. I was in trouble. My mother, in the Falcon, was still ahead of me. She didn’t know. I pulled into the westbound lane, into the glare, and gunned it.

When I opened my eyes, a loose section of the fog was like a gauze over the sun. I knew where I was. I knew Chulo, the Jesus Saves bus’s driver, delivering flowers for my father’s memorial, knew the truth.

…

Various accounts of the accident had appeared in both San Diego papers and Oceanside’s Blade Tribune. The Fallbrook Enterprise wouldn’t have its version until the next day, Wednesday, as would the North County Free Press. All the papers had or would have the basic truth of what happened. What was unknown was who was driving the car that Detective Lieutenant Joseph Jeremiah DeFreines avoided. “A gray sedan, possibly European” seemed to be the description the papers used.

” The San Diego Sheriff’s Office and the California Highway Patrol share jurisdiction over this part of the highway. Detective Lieutenant Brice Langdon of the Orange County Sheriff’s Office is acting as a liaison with the Highway Patrol in investigating the fatal incident.”

Despite the distractions, what I was thinking was that Chulo knew the truth.

Chulo would be depositing the four new bouquets in the foyer, flowers already filling one wall. I looked in that direction, panning across the mourners. The groups in the living room were almost all men. Most were drinking rather than eating. Most of the groups of women were gathered in the kitchen.

A woman wearing a white apron over a black dress brought out a side dish of, my guess, some sort of yam/sweet potato thing. Because I was looking at her, she looked at the dish and looked at me, her combination of expression and gesture inviting me to “try some.” There was, I believed, an “It’s delicious” in there. Orange and dark green things, drowning in a white sauce.

“Looks delicious, Mrs. Wendall.”

Two kids, around ten and twelve, both out of breath, suddenly appeared at the big table, both grabbing cookies, the elder sibling tossing a powdered sugar-covered brownie, whole, into his mouth, the younger brother giving a cross-eyed assessment of his mother’s casserole.

“Larry Junior,” Mrs. Wendall half-whispered as she shooed her sons out the door. She looked at her husband, leaning against a sideboard serving as a bar. He followed his boys out the door with the drink in his hand, half-smiled at his wife, as if children running through a wake is normal; and was no reason to break from chatting with the other detective at the Vista substation, Daniel Dickson, and one of the ‘College Joe’ detectives from Downtown. War stories, shop talk. Enjoyable. Ties were loosened and coats unbuttoned, the straps for shoulder holsters occasionally visible.

“Just like on TV” my father would have said. “Ridiculous.”

Freddy, out of breath, came out of the kitchen, weaving through the wives and daughters who were busily bussing and washing and making plates and silverware available for new guests. I handed him two cookies before he grabbed them. He grabbed two more.

“They went thataway, Freddy,” Detective Dickson said, pointing to the foyer.

Freddy pushed the screen door open, sidestepped Chulo, and leapt, shoeless, from the porch to what passed for our lawn, Bermuda grass taking a better hold in our decomposed granite than the Kentucky bluegrass and the failing dichondra.

Chulo, holding a metal five-gallon bucket in each hand, walked through the open door and into the foyer. He was greeted by a thin man in a black suit coat worn over a black shirt with a Nehru collar. The man had light brown hair, slicked back, and no facial hair. He was wearing shoes my father would refer to as, “Italian rat-stabbers.” Showy. Pretentious. Expensive fashion investments that needed to be worn to get one’s money’s worth.

Chulo had looked at me, looked at the man, and lowered his head. The man looked at me. I didn’t lower my gaze. I tried to give him the same expression he’d given me. Not acknowledgement. Questioning, perhaps.

Langdon. He must have been at the funeral, but I hadn’t felt obligated to look any of the attendees in the eye. “Langdon,” one of the non-cop people from the Downtown Sheriff’s Office, records clerks and such, whispered. “Brice Langdon. DeFreines called anyone from Orange County ‘Disneycops.’” Chuckles. “They put people in ‘Disney jail’,” another non-deputy said.

“Joint investigation guy,” one of the background voices said. “Joint,” another one added. Three people chuckled. Glasses tinkled. Someone scraped someone else’s serving spatula over another someone else’s special event side dish. Probably not the yams.

Chulo took the arrangements out of the buckets and rearranged the vases against the wall and those narrowing the opening to the living room. He plucked some dead leaves and flowers, tossed them in one of the buckets, backed out onto the porch, closed the door. I became aware that I had looked in that direction for too long. Self-consciousness or not, people were, indeed, looking at me. Most looked away when I made eye contact.

“If you have to look at people, look them straight in the eye,” my father told me, “Nothing scares people more than that.”

Langdon looked away first, turning toward the two remaining detectives at the Vista substation, Wendall and Dickson, Larry and Dan. They both looked at Langdon, critically assessing the Orange County detective’s fashion choices. I didn’t see Langdon’s reaction.

My father’s partners had changed out of the dress uniforms they had worn at the funeral and into suits reserved for public speaking events and promotions, dark-but-not-black. Both wore black ties, thinner or wider, a year or two behind whatever the trend was. Both had cop haircuts, sideburns a little longer over time. Both had cop mustaches, cropped at the corners of their mouths, and bellies reflecting their age and their relative status. Both had changed out of the dress uniforms they’d worn at the funeral

Wendall was, in some slight apology for his height, hunched over a bit, still standing next to the sideboard that usually held my mother’s collection of display items; photos and not-to-be-eaten-off-of dishes. Dickson was acting as official bartender. The hard stuff, some wine, borrowed glasses. The beer was in the back yard.

Langdon had brought his own bottle. Fancy label, obviously expensive wine, cork removed, a third of it gone. Langdon’s thin fingers around the bottle’s neck, he offered it to Dickson. Smiling, politely, Dickson took a slug and reoffered it to Langdon. Langdon declined. Dickson pushed the bottle into a forest of hard liquor and Ernest and Julio’s finest. Langdon shrugged and looked around the room. Dickson displayed the smirk he’d saved, caught by Wendall and me.

Langdon saw my expression and turned back toward Dickson. The smirk had disappeared. Langdon walked toward me. He smiled; so, I smiled.

“I’ve heard about you,” he said. The reaction I had prepared and practiced disappeared. I was pretty much just frozen. “I see you know…” He nodded toward the foyer. “…Julio Lopez.” Langdon didn’t wait for a response. “From the beach?” No response. “Surfers.” No response. “You and I will have to talk… soon.”

I had to respond. “How old are you, Detective Lieutenant Langdon?”wh

“I’m… twice your age.” I nodded. He nodded. “College. College… Joe.” He smiled.

I may have smiled as I looked around Langdon at Dickson and Wendall; both, like my father, twelve or more years older than Langdon, this assuming he knew I was seventeen. I did, of course consider why he would know this. Wendall gave me a questioning smile. Dickson was mid-drink.

“I don’t know if you know this… Joseph: Your father was involved an investigation… cross-county thing, involving… me.” Langdon was, again, looking straight into my eyes. I blinked and nodded, slightly. “Yes. So… if there is any irony in my being… here, it is that Joseph DeFreines was, ultimately…” Langdon was nodding. I was nodding. Stupidly. “…a fair man.”

Langdon did a sort of European head bow, snap down, snap back, and tapped me on the shoulder. I had half expected to hear the heels on his rat-stabber shoes click.

THANKS FOR CHECKING OUT realsurfers.net. Copyright 2020. All rights reserved.

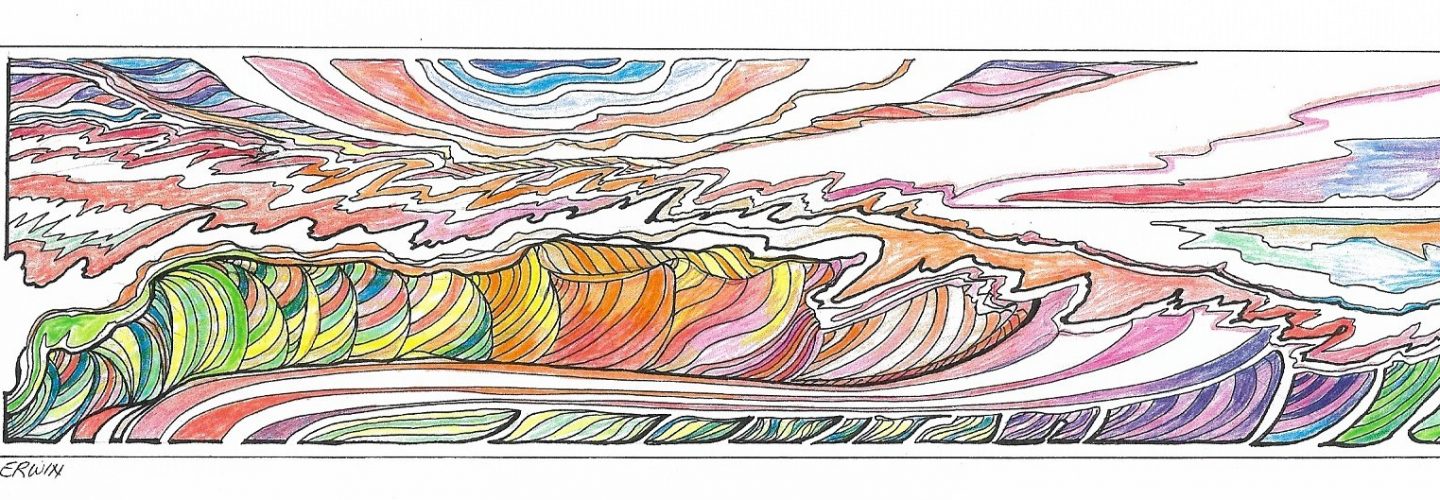

Yeah, maybe it’s hard to see the connection. Anyway, Steve promises to send me some photos of big island slabs; and continues to promise to send me some stories of Baja pirates and passports and Federales. Meanwhile, and as always, looking for those briefly- opened windows.

Yeah, maybe it’s hard to see the connection. Anyway, Steve promises to send me some photos of big island slabs; and continues to promise to send me some stories of Baja pirates and passports and Federales. Meanwhile, and as always, looking for those briefly- opened windows.