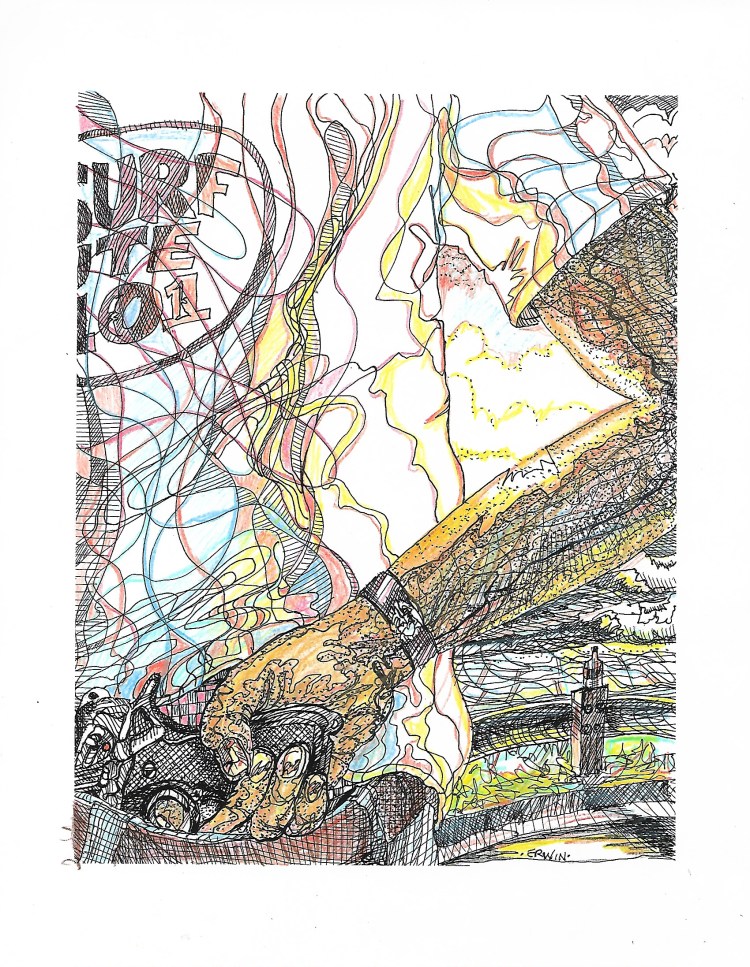

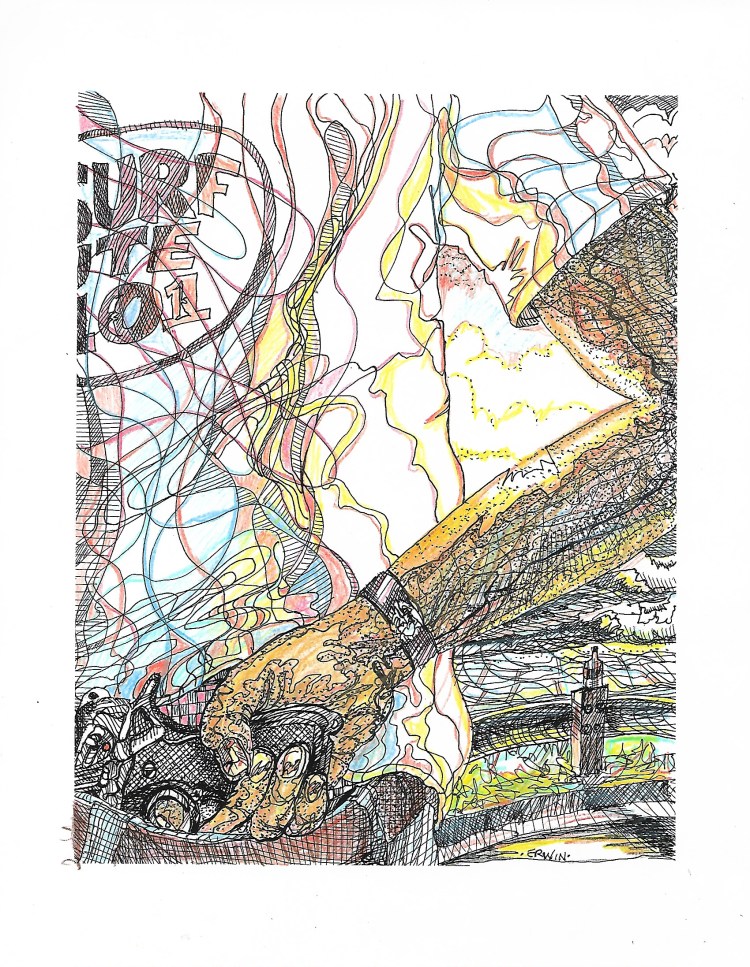

Mostly Fictional Short Stories From Surf Route 101- No One That Mattered

“‘Vietnam,’ he said; like he was impressed. ‘You, uh, um, kill anyone?'”

This was, just to clarify, my brother, Sidney, talking.

“‘No one that mattered,’ I said. I was hoping he might figure out I didn’t really mean that. Bluster. ‘Posturing,’ you’d say. ‘But, hey, man,’ I told him, ‘you’re the one with the gun.’ He looked at the old pistol, looked at me; almost smiled. Didn’t lower it, though.”

I’m still not sure why Sidney felt he had to tell me the story, but I was already picturing him, grinning; always with that grin.

Not really confessional by nature, he… we all try to have an excuse or explanation, or, something more, some justification for our actions, even those we know are wrong. This is me, then, me now; judgmental, always trying to determine what things mean.

That, introspection, that wasn’t Sidney. We, and this would be my brothers, even our dad, we tried to justify for him.

Sid continued.”Maybe I shouldn’t have let it out that I recognized Humberto; maybe… I was really just trying to save the two surfers from West Covina.”

I’m sure I nodded; support; no, just to show I had heard what Sid was saying; definitely something short of approval. My approval, I thought, at the time, is what my older brother was looking for.

At the time. Sidney was standing in the driveway when we, that’d be Julie and I, were still at the condo; before our first kid. Maybe picture me, a younger me, cleaning out my side of the shared garage; Sid pulling the Surfboards Hawaii out of the back of his jacked-up, four wheel drive truck. Twin fin; six-four, red; one of their last boards before they closed the shop; at least the one in Encinitas. The board would be worth a fortune if I still had it.

“Just tell her you bought it from me,” he said.

“With what money, Sid?”

“Future money, man.” At this he did a sort of succession of non-surfer’s surf moves, grinning, watching me the whole time.

Maybe, now that I’ve (finally) started (resumed, really) writing this… maybe what he was looking for in my expressions, and he considered himself a master of reading people; if not approval; was admiration. Maybe even respect; or, at least, some hint of jealousy.

No; I’d never let him see that. I was working on being a master (not so much any more) of not being read, of not being close. Distant. Never cool; never Sidney cool. But, whether I hid it or not, I was intrigued.

Let me simplify this particular part of the Sidney Grace saga (saga, makes me chuckle); or try to: This was the early 70s, before the old section of 101 that went through San Diego’s North County ‘beach towns’ flourished rather than died from the effects of being bypassed by I-5. There were still cheap motels, marijuana was still homegrown in avocado orchards and hidden greenhouses. Scoring weed was, it seemed, less corporate. Maybe more dangerous. Maybe less dangerous; but more exciting. LSD was… I really didn’t, and don’t, know. I just had to work and I just wanted to surf: Swamis, Pipes, Grandview, Stone Steps; wherever it was best.

And I was busy. So busy. I didn’t take drugs, did smoke (for too long), but not weed (opposite of the old line, “I don’t smoke… cigarettes.” Smile cleverly); not until later, and not enough to impress even an average college freshman (or high school junior). Though friends, even good surfing friends, did get involved, none invited me into this part of their lives. I hadn’t even been good at drinking beer, wasn’t comfortable hanging out unless it was after a surf session, and then, not for long.

Decadent. Yeah, I thought that; mostly I considered it a waste of time.

So, it was fine. I was busy.

Anything I knew of a drug subculture was mostly hearsay, other people’s stories, fiction; real life embellished; stories I chose to ignore, avoid, not hear. Still, I occasionally stopped for a moment to try to make sense; always trying to have things make sense, to fit into my version.

People assumed, because of my brothers, four of them, two sisters; and who my brothers ran around with, that I knew things. I just had to know, for example, the dreadlocked white guy who was the “Luther Burbank of Dope;” who came back to Fallbrook from some secret mountain grow area; occasionally, handing out free samples.

“Bombers, righteous shit. Virgin buds,” my brother, Grace number 4, who, along with brothers one, three, and five, did know him, would tell me. “Big parties; everyone would come,” he said. “Not you, of course.” “No.” “Busy.” “Yeah.”

Even when I left home, moved to a crappy rental in Cardiff, someone would assume I knew something about inland weed. North County was that rural.

“Which Grace am I? Two,” I often had to say to random people, each with an a sort of eager, hopeful, and expectant expression, wanting to get some kind of inside information. “You’ll have to ask one of them.” No, I wasn’t being sly; wasn’t judging the person not trusted or cool enough. No, I wasn’t. This was never believed. The person was always angry, I was always a dick or an asshole. “Sorry.”

Sid was the oldest Grace. He didn’t want to be in charge, to be responsible for the rest of us when our mother died. He didn’t want to be like our father, bluecollar, to whom work is ‘so’ important. He wanted… something easier. He took two years in the Army, cannon fodder, because even junior college at Palomar was, he said, “high school with ashtrays (common putdown at the time), full of phonies, anyway, and, anyway, too much like work.”

“Fun and games,” he said, when he got back. “Easy.”

He didn’t look like it had all been easy. Most of his friends had scattered, as did most of mine. As soon as our dad remarried, I escaped, headed for the coast. The underground ‘agriculture’ economy had moved north. Grace brother number three had moved with it. He wouldn’t reveal who he worked for. Still hasn’t. “You know them,” was his explanation; “Can’t say.”

Sid was not interested in being ‘any kind of farmer.’ There were other opportunities, and there were still parties on hills, property parents had bought in the fifties sub-divided by our peers into ranchettes. There were homes, estates to build, orchards to tear out or replace, irrigation to set up. Opportunities. People from money who had more money. Easy.

That’s only part of how Sid got into a cheap motel room in Leucadia, a block back from the non-beach side of 101; with the two surfers from West Covina gagged and tied together on a bed; with Humberto Lopez and the guy with the gun to my brother’s head; with two surfboards cut open, leaning, rather politely, against a wall; several duct tape-wrapped packages on the other bed.

“You once told me that you can’t really remember pain,” Sid told Humberto, trying not to look at the gun trembling in the hand of the other Mexican. “It’s not really true, I found out…(he laughed at this point, hoping Humberto would at least smile- he didn’t)… but I held on to the notion. It helped.”

Humberto had to soften. This was Sid, confident, grinning, cool. “Yeah; I was talking about… you couldn’t believe my father wanted me to quit high school to work in the fields.”

“I couldn’t believe he had you working in the fields at fifteen.”

The young man switching the gun from hand to hand was unimpressed by that story. White guys don’t know. Sidney and Humberto remembered the story neither would tell; how the usually-slacker PE coaches would, at some random time, have some sort of ‘Hell day,’ and run and exercise the shit out of everyone. They still did it when I went through. Humberto had been suffering more than most, not keeping up. It was my brother who came to his defense.

“Okay then Hotdog; fifty burpees (four count squat thrusts), Grace. No, all you Jockstraps. Everyone. Not you, Lopez; you just relax.” The coach went to his version of a feminine voice. “Just catch your breath.”

In the garage at the condo, Sidney said of that earlier incident; “The problem with helping someone, in a moment of weakness, is, or can be, resentment. I’m just; I know you like to figure shit out. So, now I was the one who knew about Humberto’s weakness. It lingers. When he’s attempting to steal drugs, armed robbery, and that person, me; when I come barging into the room, and he doesn’t know how that’s going to turn out, and I recognize him, and remember his weakness, and…”

“Yeah, Sidney; I think I sort of get it.”

“Yeah. Sure. So, maybe we read this on each other’s faces. Hey, he recognized me first. I could tell.”

Look: I’ve thought about this story, about Sid’s version; thought about how much of it I believe.

“What’cha going to do with the bricks, Humberto? Got a plan? (pause, Humberto and his accomplice looking at each other) You and this guy, someone you work with in the… (checking their pants, dirt on the knees, maybe something caught in the folded-up cuffs) flower greenhouses? You see two white guys with… (nodding outside) four boards, but they only take two inside the motel… two newer boards? So, knowing these a-holes probably aren’t grinding out a living doing stoop labor…”

“Sidney?”

“Humberto?”

“Why are you here?”

“Your guess? Even though I yelled ‘surf’s up’ at the door, you know I don’t surf. No. My brother. One of them; he surfs. Number four, he kneeboards, some. You don’t know, Humberto; you don’t know how to get rid of a couple of bricks of… you even know what that is you’re stealing?”

“We were waiting for, I guess, you. Sid-ney.” That was the other guy speaking, waving the gun around; checking for Humberto’s reaction. It was negative, as if his co-conspirator had been disrespectful. He didn’t know Sidney.

“Yeah; so, fine.” Sidney backed up a step or two, looked at the West Covina boys, put a hand out toward the guy with the gun to calm him down, pulled a wad of bills out of his pocket, held that out [in a later telling this became two hundred dollar bills from a wallet].

“I’m sure they’ll be fine heading back to LA. I’ll give them some money for gas. Okay? I wasn’t holding on to the money anyway. It’s not like it’s mine.”

The three guys standing looked at the two surfers on the bed, stripped to their trunks, the larger one tied behind the other one, both trying to nod.

“Could’a gone butt to butt,” Sidney said to the other guy. The other guy smirked, shrugged. Sidney shrugged. “Okay. I get it.”

The other guy handed Humberto the gun, took the cash; smiling, a smile that went away when my brother reached down for the drugs [later the look was disappointment, and Humberto asked, “This it?”] Sidney threw his hands out as if this was the deal; looked back at Humberto, who released the hammer on the revolver.

My brother, in recreating this, talked really fast: “Where’d you get that pistolo, ‘Berto? And, hey, man; these drugs don’t belong to me. Either. You get that, right? They’re carriers, they work for me. I’m a carrier. Just. Only. They didn’t know what… (he looked at the boards. They were waxed- he turned toward the West Covina boys, back toward Humberto). They; guess they tried to ride the boards. Shit. See? You take these drugs and you’ve got so many new problems. I have some real weapons in my truck. What do you think we trade for drugs? Huh? Too much knowledge, man; not so good. You have no plan, man. We have to… If you… you think about how hard it is to get rid of bodies? I mean; the Sheriff’ll come lookin’ hard for two wetbacks… don’t mean that… kill a couple of innocent, white, spoiled-ass suburban surfers. Right?”

“We’ll just take the money, and…” Humberto set the old pistol on the small television set, took the money, looked to my brother. Sidney took two twenties out of his wallet, threw them on the bed, reset his grin. Humberto just wanted out.”Okay, Sid?”

“It should have been okay,” Sidney told me. “I just started thinking about all the connections.”

“Connections?”

“I thought about how this would affect me.”

“If no one found out,” I said. “The West Covina boys wouldn’t talk; Humberto and his friend…”

“Yeah, yeah; it was all rattling in my brain. I thought about… I thought about what my people would… no one wanted any attention to any kind of trafficking in those days. I kind of imagined Humberto taking the gun and…”

“And what? Kill the other guy? What, Sid?”

“‘You’ll have to work for me, Humberto,’ I said. ‘Your friend, too. You wanted it easy. Easier. Right?'”

“‘Maybe not,’ Humberto said. ‘Maybe we’ll just… (too long a pause; Humberto picked up the gun, cocked it) I don’t care about the drugs. I don’t want your kind of life, Sidney; but, really; dead drug dealers… like you said, ‘No one that mattered.’ No need to dispose of the bodies. I’m willing to leave the drugs. Or some of them.’ He took one brick.”

“‘It’s not that much money, Humberto, I said; ‘Not enough.'”

Sidney took a breath, set the Surfboards Hawaii twin fin, with removeable, adjustable rainbow fins, onto the rack of my car.

“I don’t know if I seemed weak. No, I did; it was all just so… heavy, so exhausting. Humberto…anyone could have seen this.”

“So… what did happen?”

“Humberto and his buddy backed toward the door.”

“‘We’ll just call it even, then; Sidney,’ he said.”

“‘No, Humberto; not even.’ We looked at each other. If I hadn’t smiled…’Forty burpees, Humberto; and then we’ll call it even. Forever.'”

At telling this, my brother released his serious expression and laughed. So did I.

“I did twenty. Humberto did the full forty. No problem. This time he was in shape.”

Sid said Humberto got the money, a new gun, and one for his friend, Julio; the West Covina boys never came back to the North County, as far as Sid knows, and they all went out for tacos.

“Fine. Sure. The West Covina boys, too?”

“Yeah, them too.” Both of us were laughing when Julie came into the garage, looked at the Surfboards Hawaii twinfin, looked at Sidney, looked at me.

“How much,” she asked Sidney. “No presents.”

Sidney knew not to offer any more presents.

“Easy payments,” he said. “Future money.” Sidney and I both waited through Julie’s look of disapproval.

“How long, Sidney?”

“The payments. Easy…”

“No; how long are you going to…”

Sidney seemed to think through all his previous arguments about his life, mine, our father’s; all in a moment. He nodded, and said… nothing. He shrugged. Then Julie shrugged, looked at me. I shrugged.

“Fun and games,” she said, to both of us. “I have some cash in the…” She looked at the board I was now holding, moving it through the air as if it was on a wave. Sidney watched with something short of understanding; not jealousy, really, except, maybe, he might have been just a bit envious that this simple act could make me so happy. “Nice board,” Julie said.

You can’t know how I’d love to leave the story here. I heard a slightly different version of the Leucadia motel incident, years later, from Humberto.

“Sidney Grace always told me he didn’t expect to live well AND long,” Humberto said, at the makeshift memorial at my dad’s house. Everything else was hushed, to one side; secrets.

“It was very tense. Sid asked me…it was a test… I didn’t know that… what I was willing to do if I, if I went to work with him. I had said I was willing to kill him and the two surfers. Bluff. I wanted, so bad, to be out of there. A mistake. He asked me if, instead, I’d be willing to kill Julio. He acted like he meant it. I pointed the gun at him. Julio. ‘Sidney,’ I said, ‘I would, but he’s married to my sister. I’d have a hard time explaining it.’ ‘So, no?’ ‘No.’ Your brother acted like he was putting the wallet back in his… That’s when Sid knocked the gun out of my hand, pulled one out from… it was behind his back. ‘You owe me, ‘berto;’ he said. I practically shit myself. Umm; I still think Julio did.”

We pause for a moment; our laughter only a bit out of place. Still, I stopped, looked around the room. Half the people there were… altered. The former Luther Burbank of Weed, bald and overweight, was talking with Grace number four, chuckling occasionally. Julie had just put a hand on my father’s shoulder. He stopped crying, smiled.

“So your brother says, ‘Forty burpees, Hotdog. Now!’ He did, maybe, five. Julio, he…”

We were laughing again; but we both stopped when Grace Number 5 and another law enforcement type came over. “Nice to see you again,” my last brother said, reaching out a hand; “Deputy Lopez.”

The last Grace looked at me, tipped his just-emptied wine glass toward me, said, “Not your fault.”

If my brother and Humberto tried to read my expression at this moment… they did; I just… it didn’t matter.

Since I wasn’t planning on working, I dropped Julie and the kids off, checked out Pipes from the parking lot. A little crowded. A little choppy. Went out anyway.

Partway through the drawing I decided to add the coffee. I totally lost control after that.

Partway through the drawing I decided to add the coffee. I totally lost control after that.