CHAPTER FIVE- TUESDAY, MARCH 4, 1969

It was still early afternoon. I was in the living room, ignoring everything behind me, facing but not really seeing anything out the large, west-facing window. A Santa Ana condition had broken down, and a thousand-foot-high wall of fog had pushed its way up the valleys. The house was situated high enough that the cloud would occasionally clear away, the sun brighter than ever. The heat and humidity, raised by the number of people in our house, caused a fog of condensation on the plate glass.

Below me, cars were parked in a mostly random way in the area between the house and the separate and unfinished garage, and the corral. Continued use had created a de facto circular driveway up the slight rise from the worn and pitted gravel driveway and across the struggling lawn to the concrete pad at the foot of the wooden steps and front porch.

A bright yellow 1964 Cadillac Coupe De Ville convertible, black top up, was parked closest to the door. This was the car my mother and brother and I rode in from the funeral. Other vehicles were arranged just off the driveway, on the clumpy grass that filled in areas of ignored earth on its own. Later arrivals parked on the lower area.

Parking. I have some sort of obsession with getting in, getting out, getting away.

I was vaguely aware of the music coming from the stereo radio and turntable built into the Danish modern console in the living room. I was slightly more aware of the conversations among the increasing crowd. Little groups were spread around the room, some louder than others. Praise and sympathy, laughs cut short out of respect. Decorum.

Someone had put on a record of piano music; Liberace, or someone. This would not have been my father’s choice of music. His would have been from the cowboy side of country/western; high octave voices capable of yodeling, lonesome trails and tumbling tumbleweeds, the occasional polka. It wasn’t my mother’s choice, either. She preferred show tunes with duets and ballads by men with deep, resonant voices, voices like her husband’s, Joseph Jeremiah DeFreines.

These would not have been my father’s choice of mourners. “Funerals,” he would say, “Are better than weddings.” Pause. “You don’t need an invite or a gift.”

Someone behind me was repeating that line, mistiming the pause, his voice scratchy and high. Not high, just not my father’s voice. “Joseph,” the man said. I turned around. Yes, it was Mister Dewey. A high school social studies teacher, he sold insurance policies out of his rented house on Alvarado. His right hand was out. I was not shaking hands on this day. I didn’t believe it was to be expected of me. “You know my daughter, Penelope.”

“Penny,” I said. “Yes, since… third grade.” Penny, in a black dress, was beside Mr. Dewey, her awkwardness so much more obvious than that of the other mourners. I did shake her hand. “Penny, thanks for coming.” I did try to smile, politely. Penny tried not to. Braces.

Remembering an incident in which Mister Dewey was involved, I stared at him too closely, for too long, trying to determine if he was remembering it. Also. I believed he was.

Ten seconds, maybe. When I refocused, Mister Dewey and the two people he had been talking with previously, a man and woman who wasn’t Mrs. Dewey, were several feet over from where they had been. The woman and Penelope Dewey were looking at me. Mr. Dewey and the man were not. I smiled at the woman. She half-smiled and turned away. She wasn’t the first to react this way. If I didn’t know how to look at the mourners, many of them did not know how to look at me, troubled son of the deceased cop.

If I was troubled, I wasn’t trying too hard to hide it. I was trying to maintain control. I moved, more sideways than backwards, to the window. It was not a good time for me to freeze, to disappear into a memory at the memorial for my father. The wake.

Too late.

“Bleeding heart liberal, that Mister Dewey,” my father was telling my mother, ten-thirty on a school night, me still studying at the dinette table. “He figures we should teach sex education. I told him that we don’t teach swimming in school, and that, for most people, sex… comes… naturally. That didn’t get much of a laugh at the school board meeting.”

“Teenage pregnancies, Joe.”

“Yes, Ruth.” My father touched his wife on the cheek. “They change lives. But…”

“Freddy and I both took swimming lessons at Potter Junior High, Dad. Not part of the curriculum, but…”

“Save it for college debate class, Jody; we grownups… aren’t talking about swimming.”

Taking a deep breath, my hope was that the mourners might think it was grief rather than some affliction. Out the big window, a San Diego Sheriff’s Office patrol car was parked near where our driveway hit the county road. The uniformed Deputy, Wilson, assigned to stand there, motioned a car in. He looked around, went to the downhill side of his patrol car. He opened both side doors and, it had to be, took a leak between them. Sure. Practical.

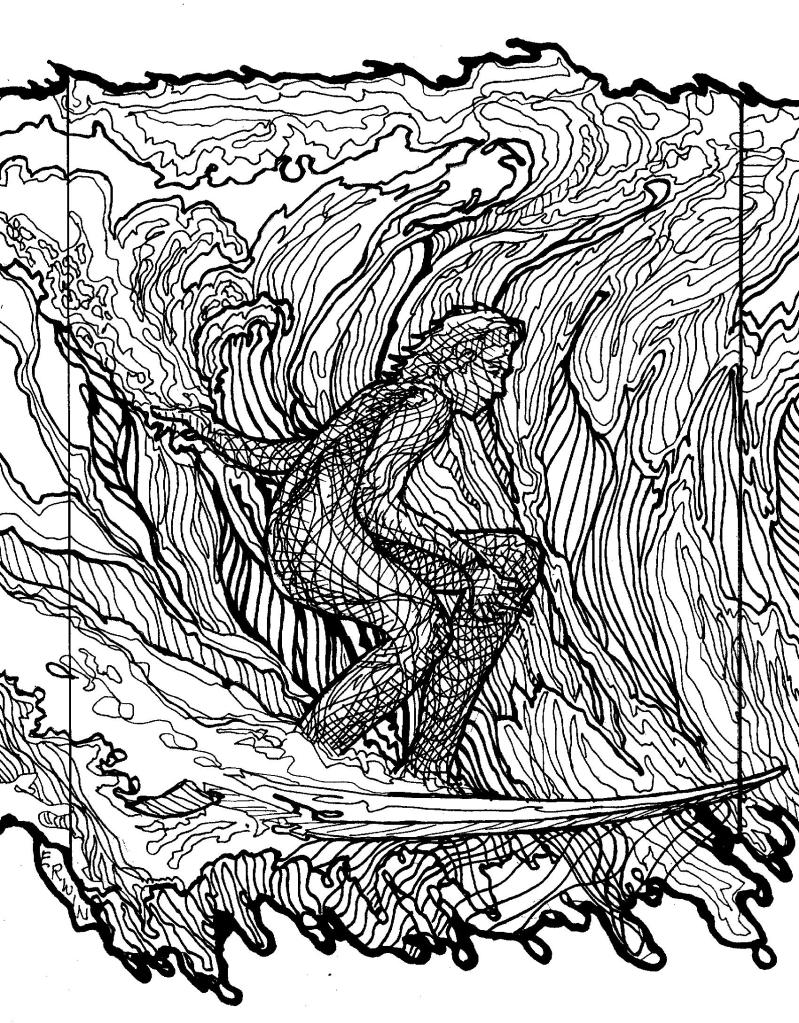

The next vehicle, thirty or so seconds later, was a delivery van painted the same bright yellow as the Cadillac. I noticed the surfboards on the roof as the Deputy waved it through. Two fat, early sixties popout surfboards, somewhere around nine-foot-six, skegs in the outdated ‘d’ style. One board was an ugly green, fading, the other had been a bright red, now almost pink. Decorations, obviously, they appeared to be permanently attached to a bolted-on rack. The van was halfway to the house before I got a chance to read the side. “Flowers by Hayes brighten your days.” Leucadia phone number.

Hayes, as in Gustavo and Consuela Hayes. As in Jumper Hayes.

A man got out of the van’s driver’s seat, almost directly below me. Chulo. I knew him from the beach. Surfer. Evangelist. Reborn. Jumper’s friend before the incident that sent them both away.

Chulo’s long black hair was pulled and tied back; his beard tied with a piece of leather. He was wearing black jeans, sandals, and a t-shirt with “Flowers by Hayes” in almost-chartreuse, day-glow letters. Chulo looked up at the window, just for a moment, before reaching back into the front seat, pulling out an artist’s style smock in a softer yellow. He pulled it over his head, looked up for another moment before limping toward the back of the van.

The immediate image I pulled from my mental file was of Chulo on the beach, dressed in his Jesus Saves attire: The dirty robe, rope belt, oversized wooden cross around his neck. Same sandals. No socks.

That wasn’t enough. I looked into the glare and closed my eyes.

Though I was in the window with forty-six people behind me, I was gone. Elsewhere.

I was tapping on the steering wheel of my mother’s Volvo, two cars behind my Falcon, four cars behind a converted school bus, “Follow me” in roughly painted letters on the back. The Jesus Saves bus. It was heading into a setting sun, white smoke coming out of the tailpipes. We were just east of the Bonsall Bridge. The bus was to the right of the lane, but moving forward. One car passed, the Falcon passed, the car behind it, all disappearing into the glare. The cars in front of me were going for it. I gunned it.

I was in the glare. There was a red light, pulsating, coming straight at me. There was a sound, a siren, blaring. I was floating. My father’s face was to my left, looking at me. Jesus was to my right, pointing forward. This wasn’t real. I had to pull out of this. I couldn’t. Not immediately. The Jesus Saves bus stopped on the side of the road, front tires in the ditch. I was looking at the ditch, at the bank beyond it. I backed the Volvo up, spun a turn toward the highway. I looked for my father’s car. I didn’t see it. The traffic was stopped. I was in trouble. My mother, in the Falcon, was still ahead of me. She didn’t know. I pulled into the westbound lane, into the glare.

When I opened my eyes, a loose section of the fog was like a gauze over the sun. I knew where I was. I knew Chulo, the Jesus Saves bus’s driver, delivering flowers for my father’s memorial, knew the truth.

…

Various accounts of the accident had appeared in both San Diego papers and Oceanside’s Blade Tribune. The Fallbrook Enterprise wouldn’t have its version until the next day, Wednesday, as would the North County Free Press. Still, the papers had the basic truth of what happened. What was unknown was who was driving the car that Detective Sergeant Joseph Jeremiah DeFreines avoided. “A gray sedan, possibly European” seemed to be the description the papers used. Because the San Diego Sheriff’s Office and the California Highway Patrol had shared jurisdiction, a task force had been formed with officers from the Orange County Sheriff’s Office. Detective Lieutenant Brice Langdon was heading the unit, actively seeking the driver of the gray sedan.

Chulo knew the truth.

Chulo would be depositing the four new bouquets in the foyer, flowers already filling one wall. I looked in that direction, panning across the mourners. The groups in the living room were almost all men. Most were drinking rather than eating. Most of the groups of women were gathered in the kitchen. One woman brought out a side dish of, my guess, some sort of yam/sweet potato thing. Because I was looking at her, she looked at the dish and looked at me, her combination of expression and gesture inviting me to “try some.” There was, I believed, an “It’s delicious” in there. I returned the favor with a “Sure thing” gesture and smile.

I wouldn’t. I didn’t. Yams and dark green things, drowning in a white sauce. No.

Two kids, around ten and twelve, Detective Lawrence Wendall’s sons, Larry Junior being the elder sibling, were shooed out of the kitchen by Mrs. Wendall. She looked at her husband, temporarily promoted to Detective Lieutenant, leaning against a sideboard with a drink in his hand. He was chatting with the other detective at the Vista substation, Daniel Dickson, and one of the ‘College Joe’ detectives from Downtown. War stories, shop talk. Enjoyable.

Wendall waved his glass toward his wife as if kids running through a wake is normal. Mrs. Wendall noticed me and pointed to the food and the plates and smiled. Again, I went with the “Sure thing.” Response. Freddy ran out of the kitchen, past Mrs. Wendall, and toward the door. Normal.

Mrs. Wendall may have wanted me to notice that the concerned neighbors and friends were using real plates that members of another group of wives and daughters were busily bussing and washing and making available for new guests. She may have been checking to see if I was doing anything other than “Holding up.” I mouthed “Fine,” and nodded, and made gestures suggesting I was already full, and that the food was delicious.

If it was expected that children of anyone only recently deceased should let mourners know they shouldn’t let our sorrow ruin their day, I was trying.

Freddy pushed the door from the foyer to the porch open, sidestepped Chulo, and leapt, shoeless, from the porch to what passed for our lawn, Bermuda grass taking a better hold in our decomposed granite than the Kentucky bluegrass and the rapidly failing dichondra.

Chulo, holding a five-gallon bucket in each hand, walked through open door and into the foyer. He was greeted by a thin man in a black suit coat worn over a black shirt with a Nehru collar. The man had light brown hair, short and slicked down, and no facial hair. He was wearing shoes my father would refer to as, “Italian rat-stabbers.” Showy. Pretentious. Expensive. Fashion investments; need to be worn to get one’s money’s worth.

Langdon was my guess. He must have been at the funeral, but I hadn’t felt obligated to look any of the attendees in the eye. “Langdon,” one of the non-cop people from the Downtown Sheriff’s Office, records clerks and such, whispered. “Brice Langdon. DeFreines called anyone from Orange County ‘Disneycops.’ Especially Langdon and his… former partner.” Chuckles. “They put people in ‘Disney jail’,” another non-cop said.

Langdon looked across the room. Chulo lowered his head when their eyes met.

“Joint task force,” one of the background voices said. “Joint,” another one added. Three people chuckled. Glasses tinkled. Someone scraped someone else’s serving spatula over another someone else’s special event side dish. Probably not the yams.

Chulo took the arrangements out of the buckets and rearranged the vases against the wall and those narrowing the opening to the living room. He plucked some dead leaves and flowers, tossed them in one of the buckets, backed out onto the porch, closed the door. I became aware that I had looked in that direction for too long. Self-consciousness or not, people were looking at me. Most looked away when I made eye contact.

Langdon didn’t. He gave me a sort of pained smile.

“If you have to look at people, look them straight in the eye,” my father told me, “There’s nothing that scares people more than that.”

The other two detectives at the Vista substation, Wendall and Dickson, Larry and Dan, did not look away from me. They looked at Langdon. I didn’t see his reaction. My father’s partners were wearing their funeral and promotion suits, with black ties thinner or wider, a year or two behind whatever the trend was. Both had cop haircuts, sideburns a little longer over time. Both had cop mustaches, cropped at the corners of their mouths, and bellies reflecting their age and their relative status. Both had worn dress uniforms at the funeral.

Wendall was, in some slight apology for his height, hunched over a bit and leaning against the far wall next to the sideboard that usually held my mother’s growing collection of trinkets. Dickson had moved some of my mother’s collectibles and was acting as official bartender. The hard stuff, some wine, borrowed glasses. The beer was in the back yard.

Langdon had been carrying a bottle of obviously expensive wine, as if he was cool enough to not need a glass. He offered Dickson a drink. Shared, no glass. If you were cool, you’d take the offer. Dickson took the bottle, took too long a drink, and handed the bottle back, almost empty. Dickson saved the smirk until Langdon turned away. Wendall and I caught the smirks. Langdon finished the last of the bottle, set it on the main table next to the yams, and walked into the kitchen.

Wendall and Dickson looked toward me and smiled. So, I smiled. My father had been on some sort of investigation in Orange County involving Langdon. If there was an irony in his being at my father’s memorial, I was only partially aware.

I looked at the mourners as I walked toward the foyer. I would try to remember each face. I walked around the borrowed table set where our couch would have been, to my father’s chair, moved two feet over from its regular spot, oriented toward the big window rather than the TV in the console. It provided a good place to look at the people in the rooms, foyer, hallway, kitchen, living room.

The lounge chair, oversized, for once, was uncovered. The fabric was practical; heavy, gray, with just the faintest lines, slightly grayer. There was, in the seat, a matted and framed portrait I had not seen before, a photograph blown up and touched up and printed on canvas, coated with several layers of varnish. A noticeable chemical smell revealed the coating had not yet fully cured. There it was, my father in his Sheriff’s Office uniform, oversized enough that the portrait was set across the armrests.

The pose was this: Stern expression; arms crossed on his chest, low enough to reveal the medals; just the right amount of cuff extending from the coat sleeves; hands on biceps, a large scar on the palm of my father’s left hand almost highlighted. No ring. My father didn’t wear rings. Rings might have suggested my father might hesitate in a critical situation, might think of his wife and children. White gloves that should have been a part of the dress uniform were folded over my father’s left forearm. Gloves would have hidden the scar.

I didn’t study the portrait. I did notice, peripheral vision, others in the rooms were poised and watching for my reaction. I tried to look properly respectful, as if I had cried out all my tears. Despite my father disapproving of tears, I had.

There was an American flag, folded and fit into a triangular-shaped frame, leaning from the seat cushion to the armrest on one side of the portrait. A long thin box with a glass top holding his military medals, partially tucked under the portrait, was next to the flag.

If I was expected to cry, or worse; break down, to have a spell or a throw a tantrum, the mourners, celebrants, witnesses, whoever these people were, the less discerning among them, they would have been disappointed. Some, who had never saluted the man, saluted the portrait. This portrait was not the father I knew, not the man the ones who truly believed they knew him knew.

No. I walked past the detectives without looking at them, went down the hallway and opened the door to what was to have been a den. By that time, it was more storage than den. My father’s oak desk, originally belonging to the U.S. Postal Service, was elsewhere, out in the garage. I returned to the living room with two framed photographs pressed against my chest. I did my fake smile and set the portraits on the carpet, face down. I took a moment before I lifted the one on top, turned it over, and leaned it against the footrest part of my father’s chair.

Several self-invited guests moved closer, both sides of me and behind me. One of the guests said, “That’s Joe, all right.” Wendall said, “Gunner,” and toasted. Others followed suit.

This was my father. An ambered-out photo of a younger Joseph DeFreines in his parade garb; big blonde guy in Mexican-style cowboy gear, standing next to a big blonde horse with a saddle similarly decked out with silver and turquoise, oversized sombrero at his chest. My father’s other arm, his left, was around the shoulders of a smaller man, his sombrero on his head. Both were smiling as if no one else was watching.

There was no wound on my father’s left hand.

“Gustavo Hayes.” Another voice. Another asked, “What’s with Joe in the Mexican outfit?”

I lifted, turned, and leaned the other photo against the footrest. It was a black and white photo. A woman’s voice said, “Oh, Joe and Ruth. Must be their wedding.” Another woman’s voice said, “So young. And there is… something… about a Marine in his dress blues.”

“It was… taken,” I said, “in Japan, color-enhanced… painted… in San Diego.” I looked at the photo rather than at the people. My father’s arm was around his even younger bride. She was in a kimono. “The colors of the dress, my mother always said, ‘are not even close to the real colors.’ She said our memories… fill in with the… the real colors.”

I had spoken. I wanted to disappear.

…

“Swamis” copyright 2020 Erwin A. Dence, Jr. All rights reserved